Abstract

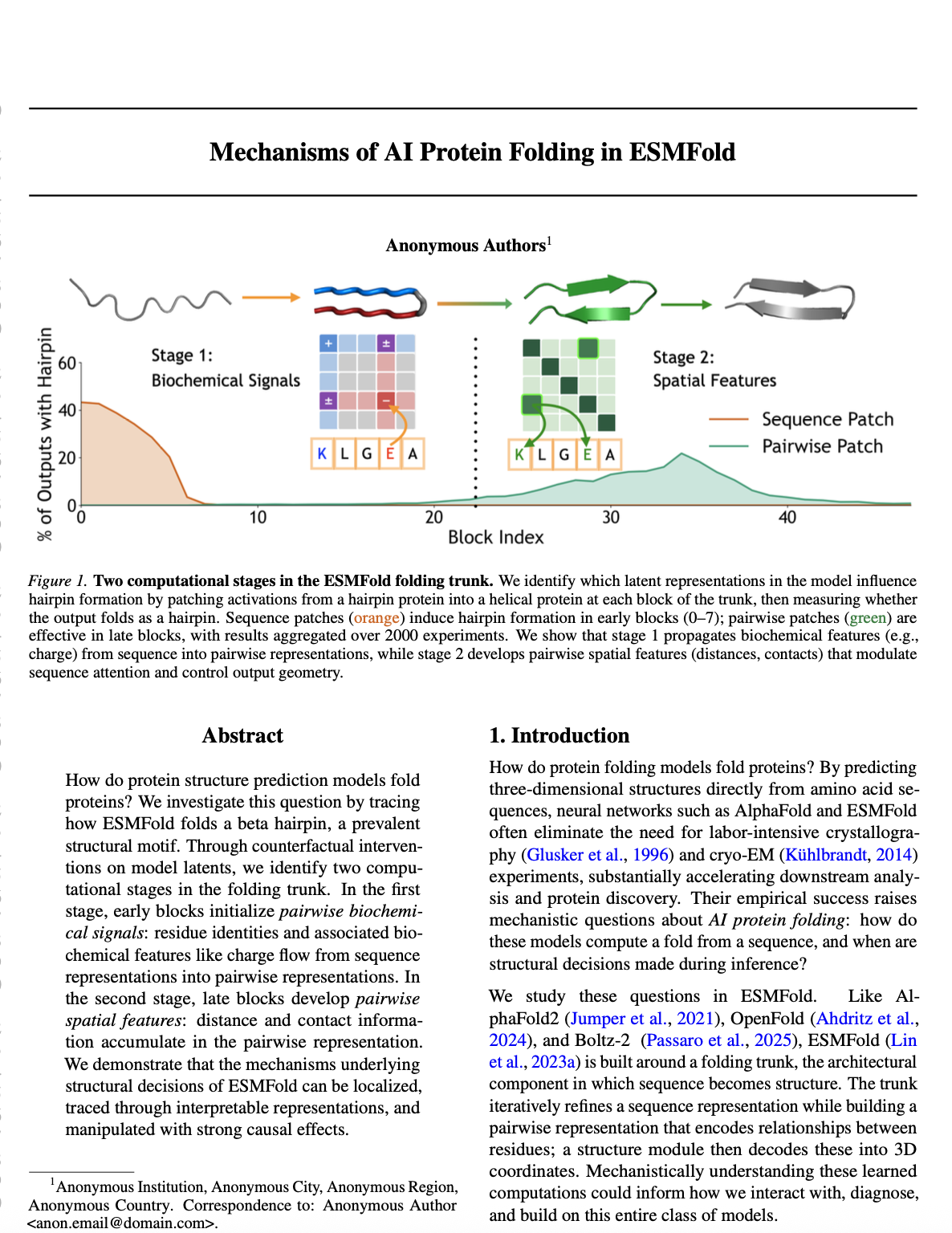

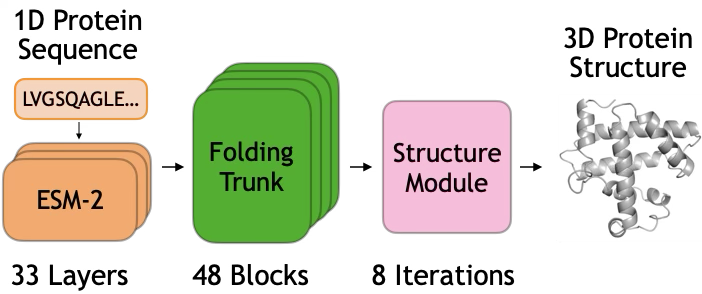

How do protein structure prediction models fold proteins? We investigate this question by tracing how ESMFold folds a beta hairpin, a prevalent structural motif. Through counterfactual interventions on model latents, we identify two computational stages in the folding trunk. In the first stage, early blocks initialize pairwise biochemical signals: residue identities and associated biochemical features like charge flow from sequence representations into pairwise representations. In the second stage, late blocks develop pairwise spatial features: distance and contact information accumulate in the pairwise representation. We demonstrate that the mechanisms underlying structural decisions of ESMFold can be localized, traced through interpretable representations, and manipulated with strong causal effects.

Introduction

How do protein folding models fold proteins? We study these questions in ESMFold. Like AlphaFold2, OpenFold, and Boltz-2, ESMFold is built around a folding trunk, the architectural component in which sequence becomes structure. The trunk iteratively refines a sequence representation while building a pairwise representation that encodes relationships between residues; a structure module then decodes these into 3D coordinates. Mechanistically understanding these learned computations could inform how we interact with, diagnose, and build on this entire class of models.

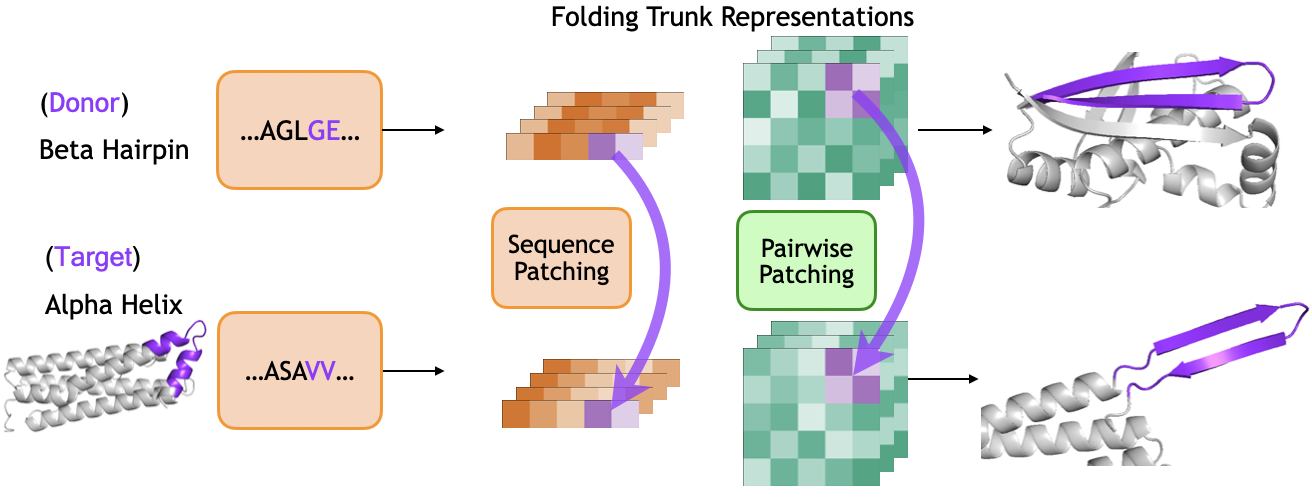

In this work, we conduct the first mechanistic analysis of a protein model folding trunk and focus on how it folds a simple and prevalent structural motif: the beta hairpin. We use activation patching to transplant sequence and pairwise representations from a donor protein containing a beta hairpin into a target protein containing an alpha-helical region. By observing whether the patched trunk produces a hairpin in the target region, we find that ESMFold folds a hairpin in two computational stages.

In the first stage, early blocks initialize pairwise biochemical signals: residue identities and associated biochemical features like charge flow from sequence representations into pairwise representations. In the second stage, late blocks develop pairwise spatial features: distance and contact information accumulate in the pairwise representation.

Background

Protein Structure

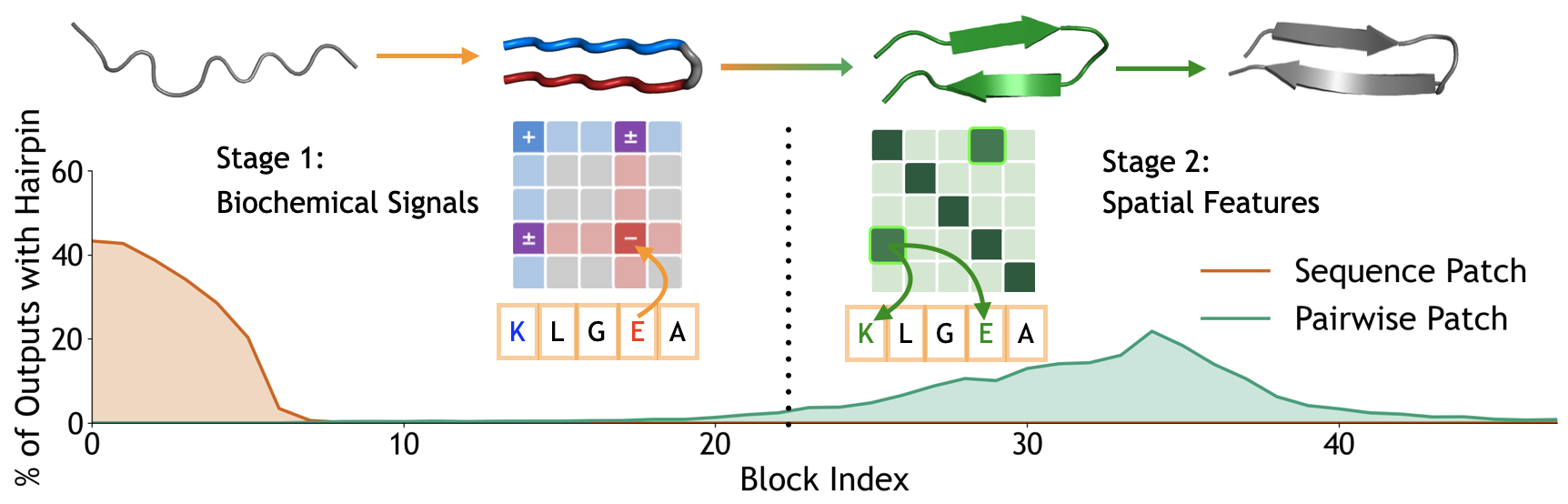

Chains of amino acids. Proteins are linear polymers of amino acids, each with a central carbon (C$_\alpha$) bonded to a backbone (N-C-C) and a variable sidechain. The sequence of amino acids defines the protein's primary structure.

Secondary structure. Local regions of the backbone adopt regular conformations stabilized by hydrogen bonds. The two most common secondary structures are alpha-helices (spiral structures) and beta-sheets (extended strands). A beta-hairpin consists of two adjacent antiparallel beta strands connected by a tight turn.

Protein Structure Prediction with ESMFold

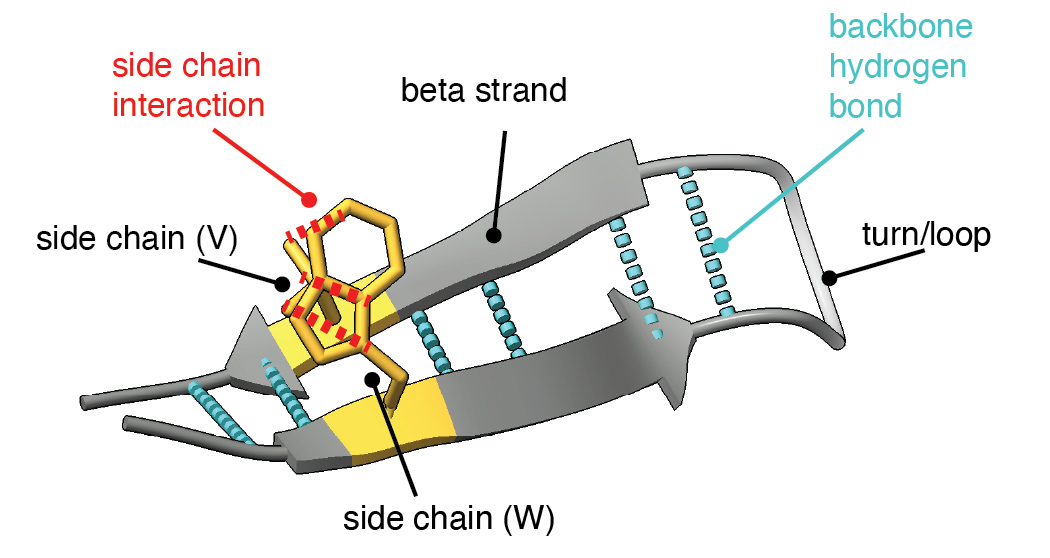

ESMFold [Lin et al., 2023] predicts protein structure from sequence alone using a two-stage architecture:

Module 1: ESM-2 Language Model. The input sequence is first processed by ESM-2, a 3B-parameter transformer pretrained on 250M protein sequences. ESM-2 produces a contextualized embedding $s_i \in \mathbb{R}^{2560}$ for each residue position $i$, capturing evolutionary and structural patterns learned during pretraining.

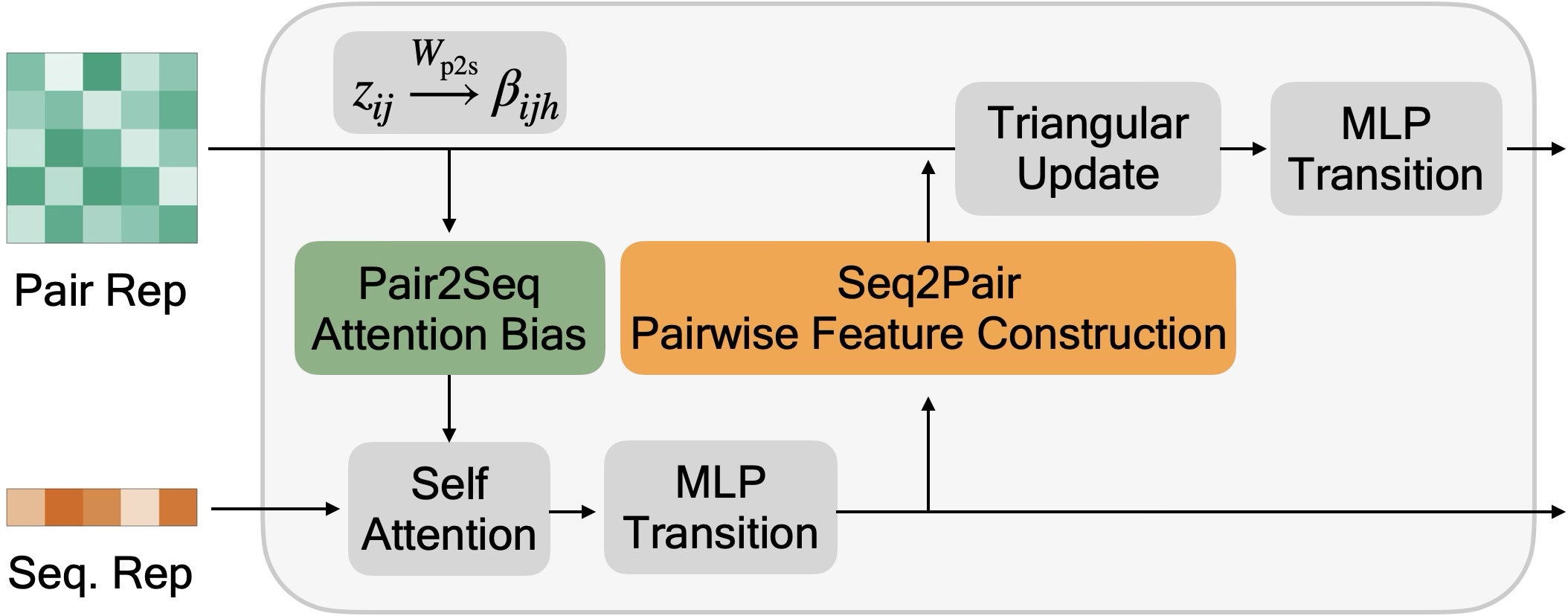

Module 2: Folding Trunk. The core of ESMFold is a folding trunk consisting of 48 stacked blocks. Each block maintains two representations:

- Sequence representation $s_i$ (per-residue features)

- Pairwise representation $z_{ij}$ (features for each residue pair)

Each folding block performs the following operations:

Sequence-to-Pair (Seq2Pair): Projects sequence features into pairwise space:

$$z_{ij} \leftarrow z_{ij} + W_{\text{out}} \cdot \text{ReLU}(W_i s_i + W_j s_j + b)$$

Pair2Seq: Aggregates pairwise features back to sequence space:

$$s_i \leftarrow s_i + W_{\text{out}} \sum_j \alpha_{ij} V_{ij}$$where $\alpha_{ij}$ are attention weights and $V_{ij} = W_V z_{ij}$.

Triangle updates and attention: The pairwise representation is updated using triangle multiplicative updates (inspired by AlphaFold2) and row/column attention to propagate constraints across the 2D grid.

Stage 3: Structure Module. After 48 folding blocks, the final pairwise representation $z_{ij}$ is passed to a structure module that predicts 3D coordinates.

When Does the Model Fold a Hairpin?

We use activation patching to localize where hairpin formation is computed in the folding trunk. We select a donor protein containing a beta hairpin and a target protein containing a helix-turn-helix motif. We run both proteins through ESMFold, extracting the sequence representation $s$ and pairwise representation $z$ at each block of the folding trunk. During the target's forward pass, we replace representations in the target's helical region with the donor's hairpin representations, aligning the two regions at their loop positions. We then observe whether the output structure contains a hairpin in the patched region.

Dataset construction. We curated a dataset of 106 target proteins consisting of alpha-helical structures from diverse protein families. For donor hairpins, we assembled a dataset of about 80,000 beta hairpins extracted from the Protein Data Bank. Each hairpin consists of two strands (5–10 residues each) connected by a short loop (2–5 residues). We identified internal loop regions in each target protein, then sampled 10 donor hairpins per loop, yielding about 5,000 patching experiments in total.

Full patching establishes feasibility. We first verify that patching can induce hairpin formation by patching both sequence and pairwise representations across all 48 blocks of the folding trunk. Approximately 40% of patches (~2,000 cases) successfully produce a hairpin in the target region, as measured by DSSP secondary structure assignment.

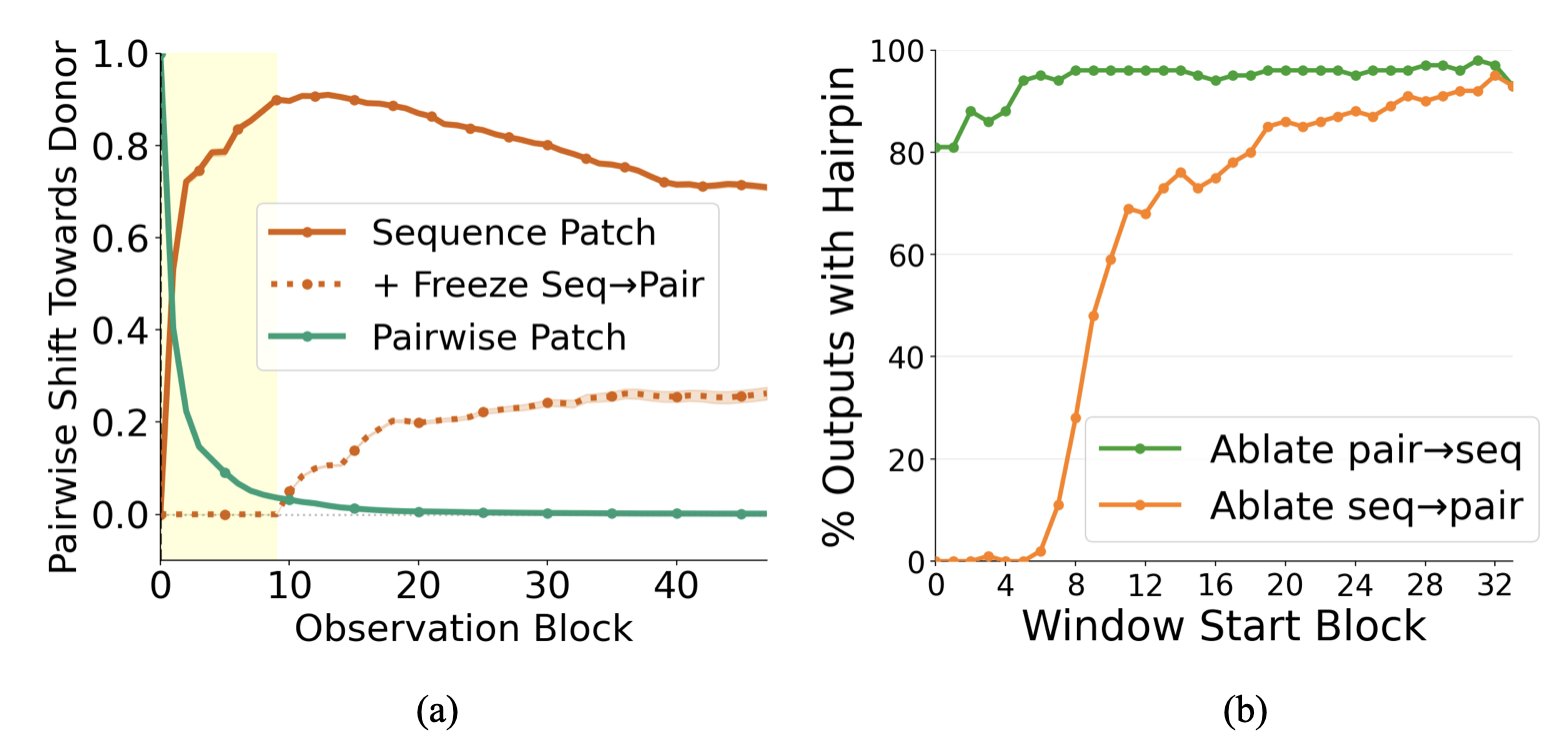

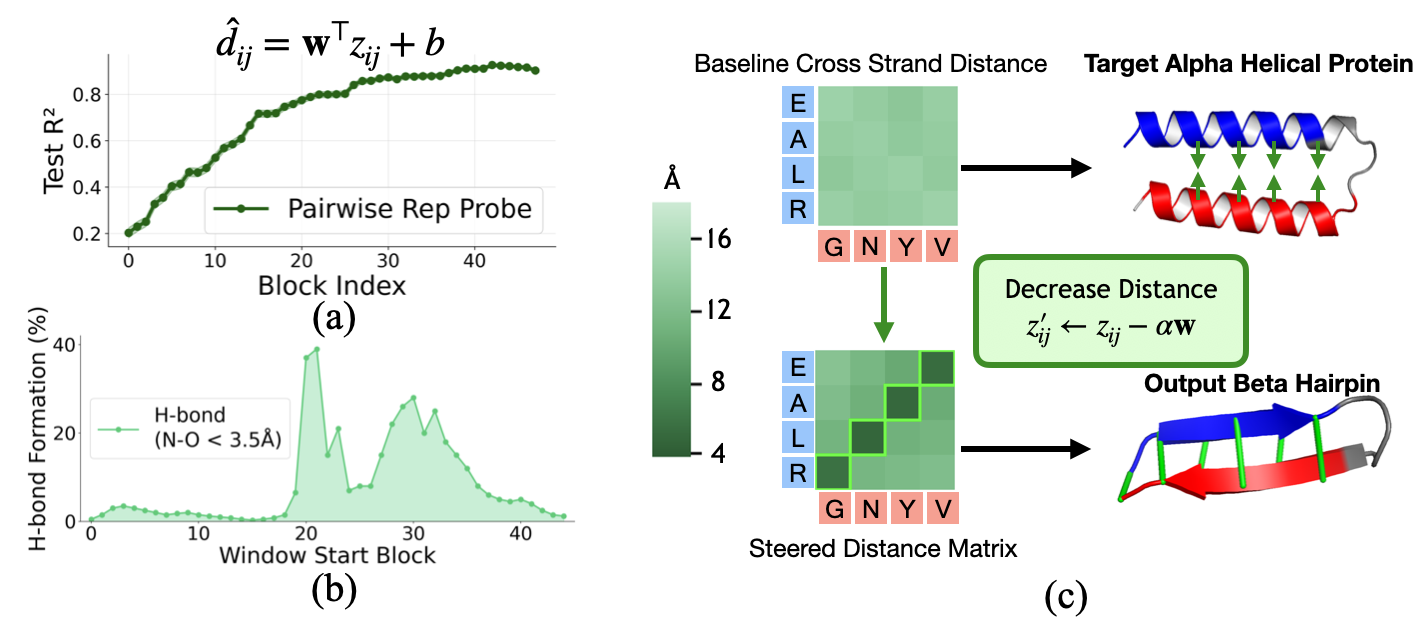

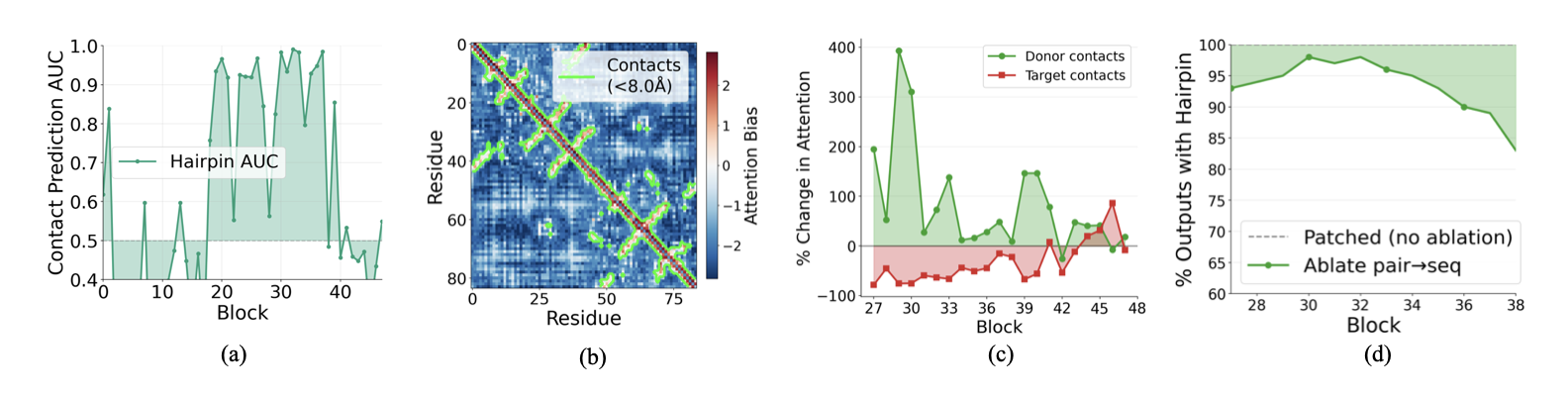

Single-block patching reveals two regimes. To localize the computation, we patch at a single block $k$, patching either sequence or pairwise representations alone. Restricting to the ~2,000 cases where full patching succeeded, we measure the success rate for each block and representation type:

- Sequence patches are effective in early blocks (0-7), with success rates peaking around 40% at block 0 and declining thereafter.

- Pairwise patches show the opposite pattern: they only become effective starting around block 25, reaching success rates around 20% by block 35.

This reveals two distinct computational stages: early blocks where sequence information drives hairpin formation, and late blocks where pairwise representations take over.

Early Blocks: Building Pairwise Chemistry

Sequence Information Flows Into Pairwise Space

Why does sequence patching only work in early blocks? We hypothesize that early blocks serve the critical role of transferring information from $s$ into $z$ via the seq2pair pathway, populating $z$ before downstream computations begin.

Representation similarity. After patching sequence at block 0, we track how the pairwise representation changes across blocks. We find that $z$ rapidly becomes donor-like in the first ~10 blocks, then changes only gradually afterward. This suggests a short early "write-in" window during which sequence-level information is transferred into $z$.

Pathway ablations. We confirm that seq2pair is necessary for hairpin formation by performing sliding-window ablations. Ablating seq2pair in blocks 0–20 dramatically reduces hairpin formation; ablating it in later blocks has little effect. This confirms that sequence patches work because they propagate into $z$ via seq2pair during early blocks.

Which Sequence Features are Propagated?

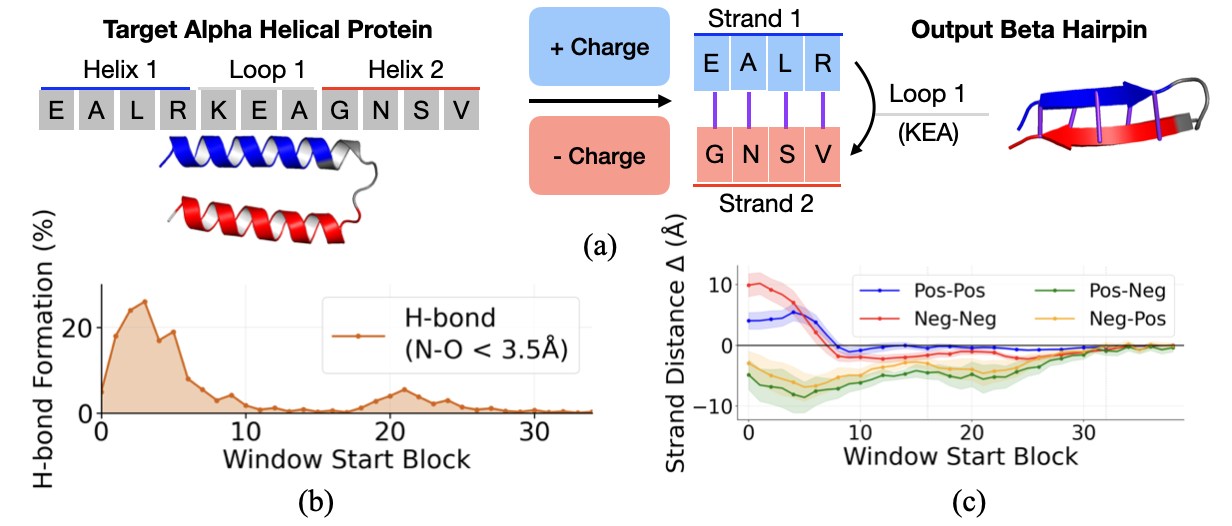

We investigate whether the model leverages biochemical features to guide folding. We focus on charge, which is biochemically relevant for hairpin stability: antiparallel beta strands are often stabilized by salt bridges between oppositely charged residues on facing positions.

Charge is linearly encoded. We use a difference-in-means approach to identify a "charge direction" in the sequence representation space. Let $\mathcal{P} = \{\text{K}, \text{R}, \text{H}\}$ denote positively charged residues and $\mathcal{N} = \{\text{D}, \text{E}\}$ denote negatively charged residues. We compute:

$$v_{\text{charge}} = \frac{\bar{s}_{\mathcal{P}} - \bar{s}_{\mathcal{N}}}{\|\bar{s}_{\mathcal{P}} - \bar{s}_{\mathcal{N}}\|}$$Projecting residue representations onto $v_{\text{charge}}$ shows clean separation between charge classes at early blocks, confirming that charge is linearly encoded.

Electrostatic complementarity steering. Because this direction is linear, we can manipulate it. For a target helix-turn-helix region, we steer one helix toward positive charge and the other toward negative charge, mimicking the electrostatic complementarity of natural hairpins:

$$s_i' = s_i \pm \alpha \cdot v_{\text{charge}}$$Result: Complementarity steering induces hydrogen bond formation, with the effect concentrated in early blocks (0–10). As a control, steering both strands to the same charge increases cross-strand distance (repulsion), while opposite charges decrease it (attraction). This confirms that the charge direction causally influences predicted geometry.

Late Blocks: Pairwise Geometry Emerges

Pairwise Representation Encodes Distance

By the late blocks, sequence patching no longer induces hairpin formation, but pairwise patching does. This suggests that the pairwise representation $z$ has taken over as the primary carrier of folding-relevant information. We hypothesize that $z$ encodes spatial relationships—particularly pairwise distances.

Distance probing. We train linear probes to predict pairwise C$_\alpha$ distance from $z$ at each block. Even at block 0, $z$ contains some distance information from positional embeddings. But as $z$ is populated with sequence information and refined through triangular updates, probe accuracy increases substantially, reaching $R^2 \approx 0.9$ by late blocks.

Distance steering. Since the probe is linear, we can steer toward a target distance (5.5Å, the typical C$_\alpha$–C$_\alpha$ spacing for cross-strand contacts in beta-sheets) by moving along the probe's weight direction:

$$z'_{ij} = z_{ij} - \alpha \cdot \mathbf{w}$$Result: Steering in blocks 20–35 is most effective, with hydrogen bond formation peaking around 40%. Steering in early blocks is less effective both because probes are less accurate and because subsequent computation can overwrite the perturbation. This confirms that late $z$ causally determines geometric outputs.

Pair2Seq Promotes Contact Information

How does distance information in $z$ influence the rest of the computation? The pair2seq pathway projects $z$ to produce a scalar bias that modulates sequence self-attention.

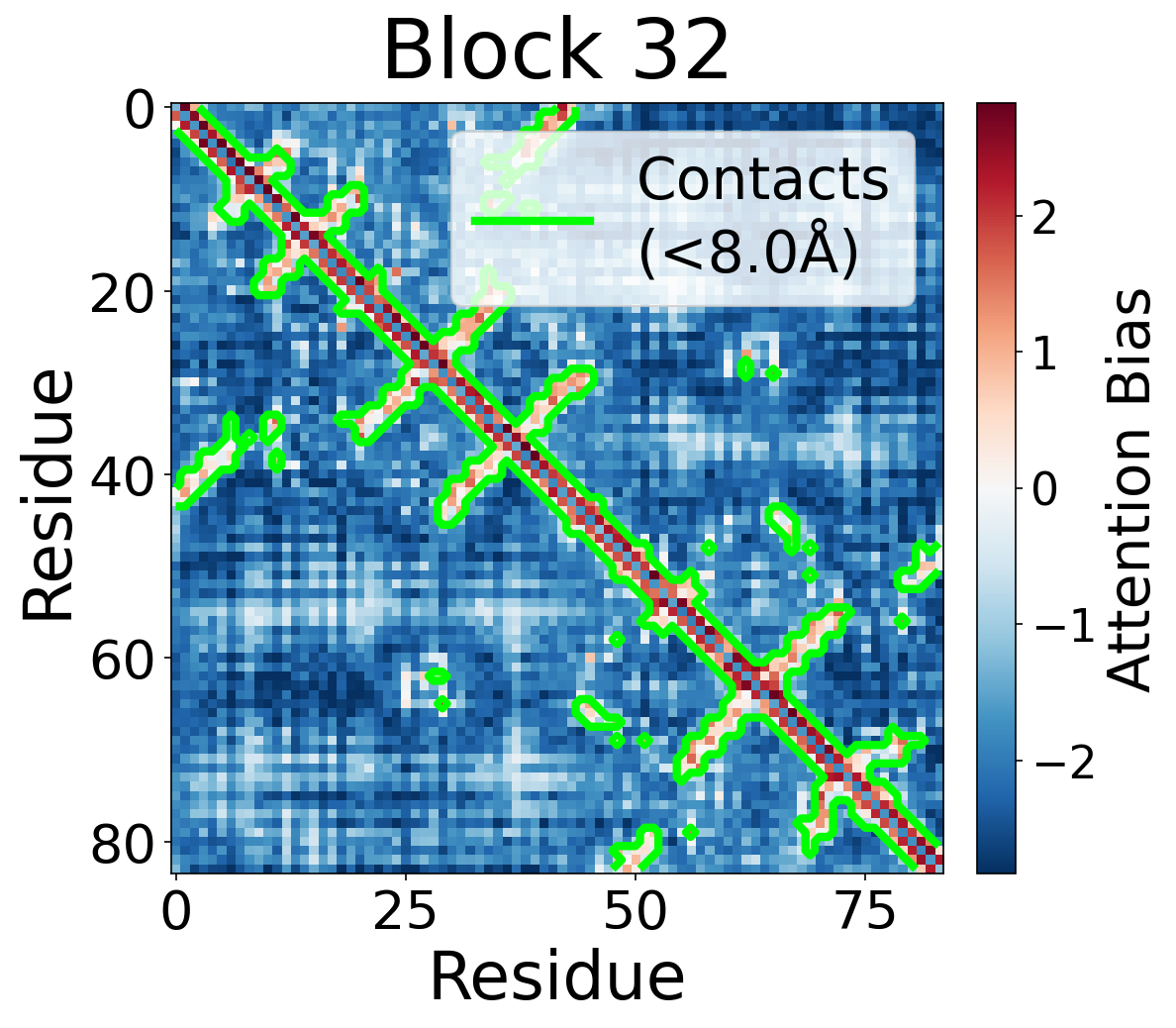

Bias encodes contacts. In middle and late blocks, the pair2seq bias cleanly separates contacting residue pairs (C$_\alpha$ distance < 8Å) from non-contacts. Residue pairs in contact receive substantially more positive bias than non-contacts, encouraging the sequence attention to preferentially mix information between contacting residues. We visualize the bias values across blocks in the Appendix, along with per-head biases which show distinct patterns and suggest head specialization as an area for future investigation.

Causal role. We tested this by patching the pairwise representation at block 27 and measuring how sequence attention changes. After patching, attention to donor-unique contacts increases substantially (up to 400%), while attention to target-unique contacts decreases. The pairwise representation causally redirects which residues attend to each other.

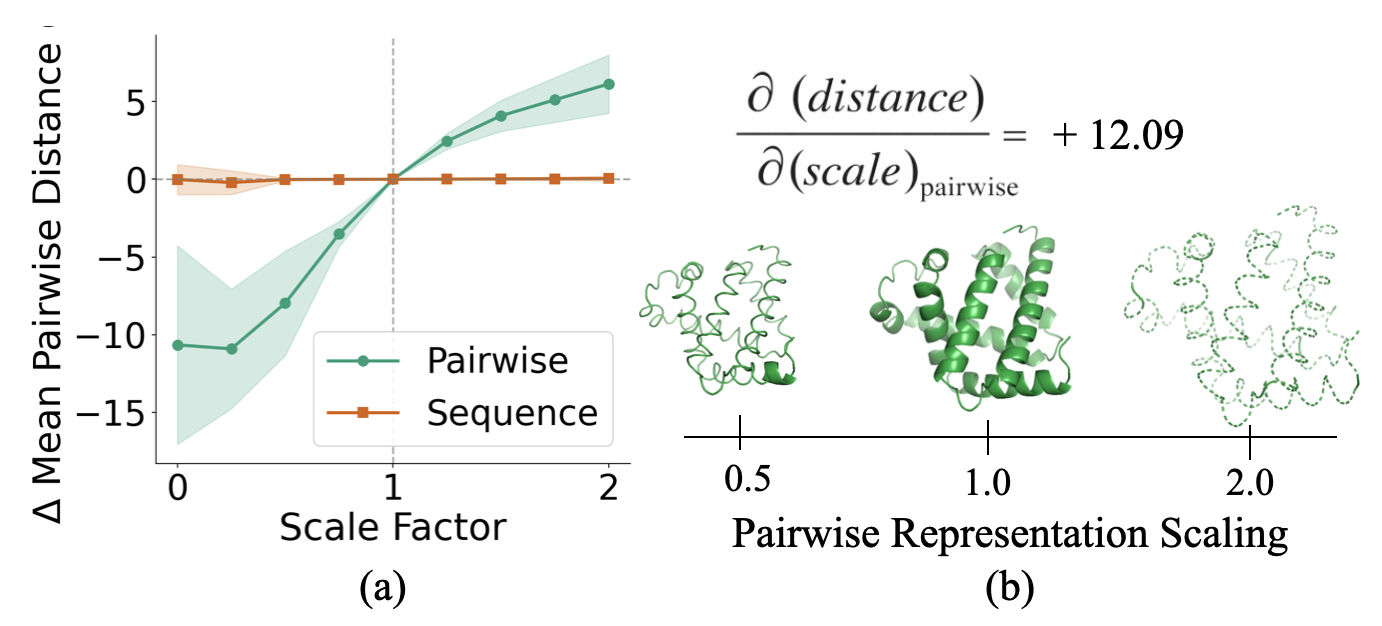

The Structure Module Uses Z as a Distance Map

The pair2seq pathway is one route by which $z$ influences the output. But $z$ also feeds directly into the structure module, which produces the final 3D coordinates.

Scaling experiment. We scaled the pairwise representation by factors ranging from 0 to 2 before it enters the structure module, while holding $s$ fixed. We then repeated the experiment scaling $s$ while holding $z$ fixed.

Result: Scaling $z$ monotonically scales the mean pairwise distance between residues in the output structure. Scaling up causes the protein to expand; scaling down causes it to contract. In contrast, scaling $s$ has virtually no effect on output geometry. Together with our steering experiments, this confirms that $z$ acts as a geometric blueprint that the structure module renders into 3D coordinates.

References

Anfinsen, C. B. (1973). Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science, 181(4096), 223-230.

Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A., Green, T., Figurnov, M., Ronneberger, O., ... & Hassabis, D. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature, 596(7873), 583-589.

Lin, Z., Akin, H., Rao, R., Hie, B., Zhu, Z., Lu, W., ... & Rives, A. (2023). Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model. Science, 379(6637), 1123-1130.

Olah, C., Cammarata, N., Schubert, L., Goh, G., Petrov, M., & Carter, S. (2020). Zoom in: An introduction to circuits. Distill, 5(3), e00024-001.

Meng, K., Bau, D., Andonian, A., & Belinkov, Y. (2022). Locating and editing factual associations in GPT. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35, 17359-17372.

Vig, J., Madani, A., Varshney, L. R., Xiong, C., Socher, R., & Rajani, N. F. (2020). BERTology meets biology: Interpreting attention in protein language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.15222.

Wang, K., Variengien, A., Conmy, A., Shlegeris, B., & Steinhardt, J. (2022). Interpretability in the wild: a circuit for indirect object identification in GPT-2 small. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.00593.

Muñoz, V., Thompson, P. A., Hofrichter, J., & Eaton, W. A. (1997). Folding dynamics and mechanism of β-hairpin formation. Nature, 390(6656), 196-199.

Dill, K. A., Ozkan, S. B., Shell, M. S., & Weikl, T. R. (2008). The protein folding problem. Annual Review of Biophysics, 37, 289-316.

How to cite

The paper can be cited as follows.

bibliography

Lu, K., Brinkmann, J., Huber, S., Mueller, A., Belinkov, Y., Bau, D., & Wendler, C. (2026). Mechanisms of AI Protein Folding in ESMFold. arXiv preprint arXiv:xxxx.xxxxx.

bibtex

@article{lu2026mechanisms,

title={Mechanisms of AI Protein Folding in ESMFold},

author={Lu, Kevin and Brinkmann, Jannik and Huber, Stefan and Mueller, Aaron and Belinkov, Yonatan and Bau, David and Wendler, Chris},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2602.02620},

year={2026}

}

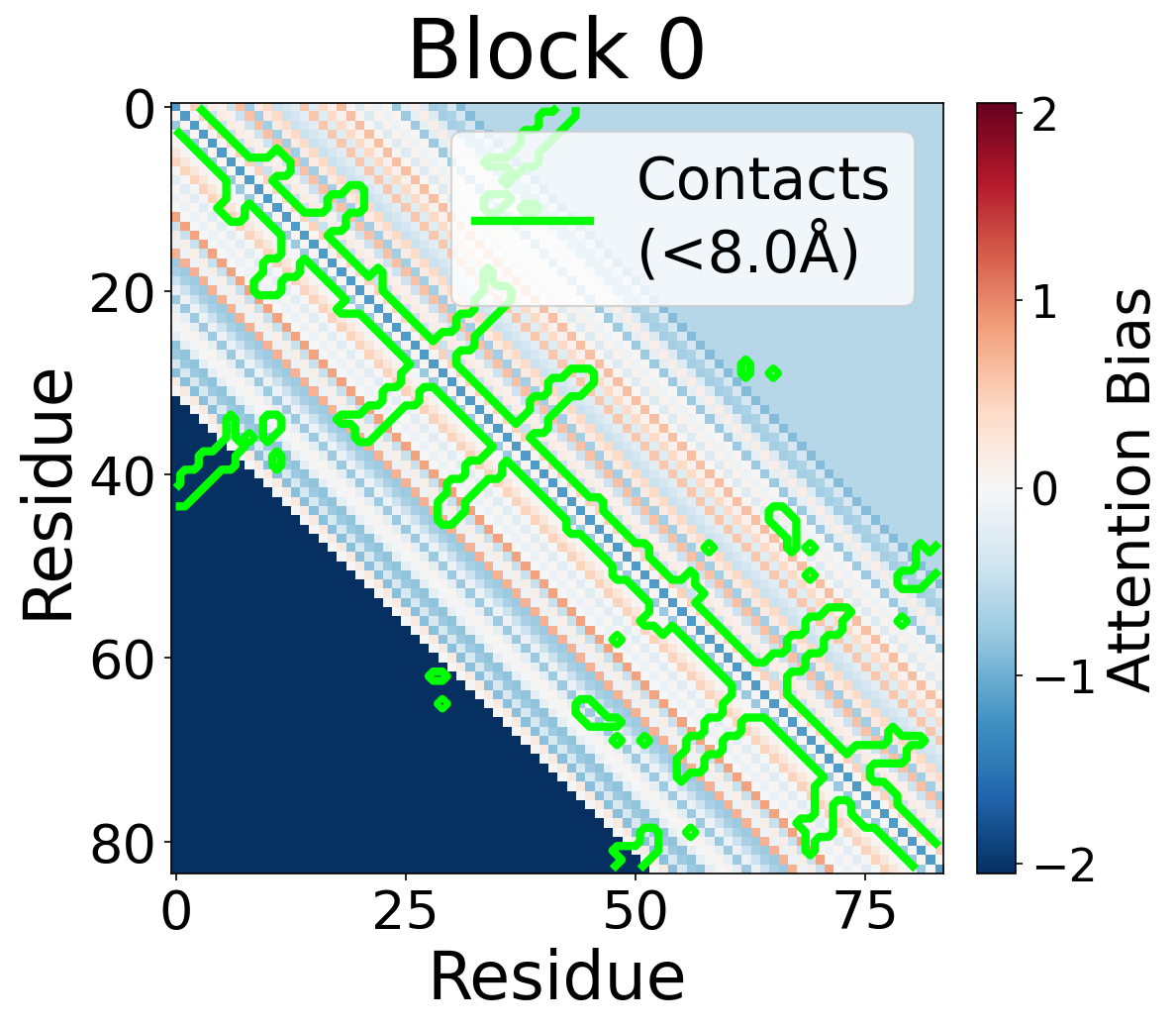

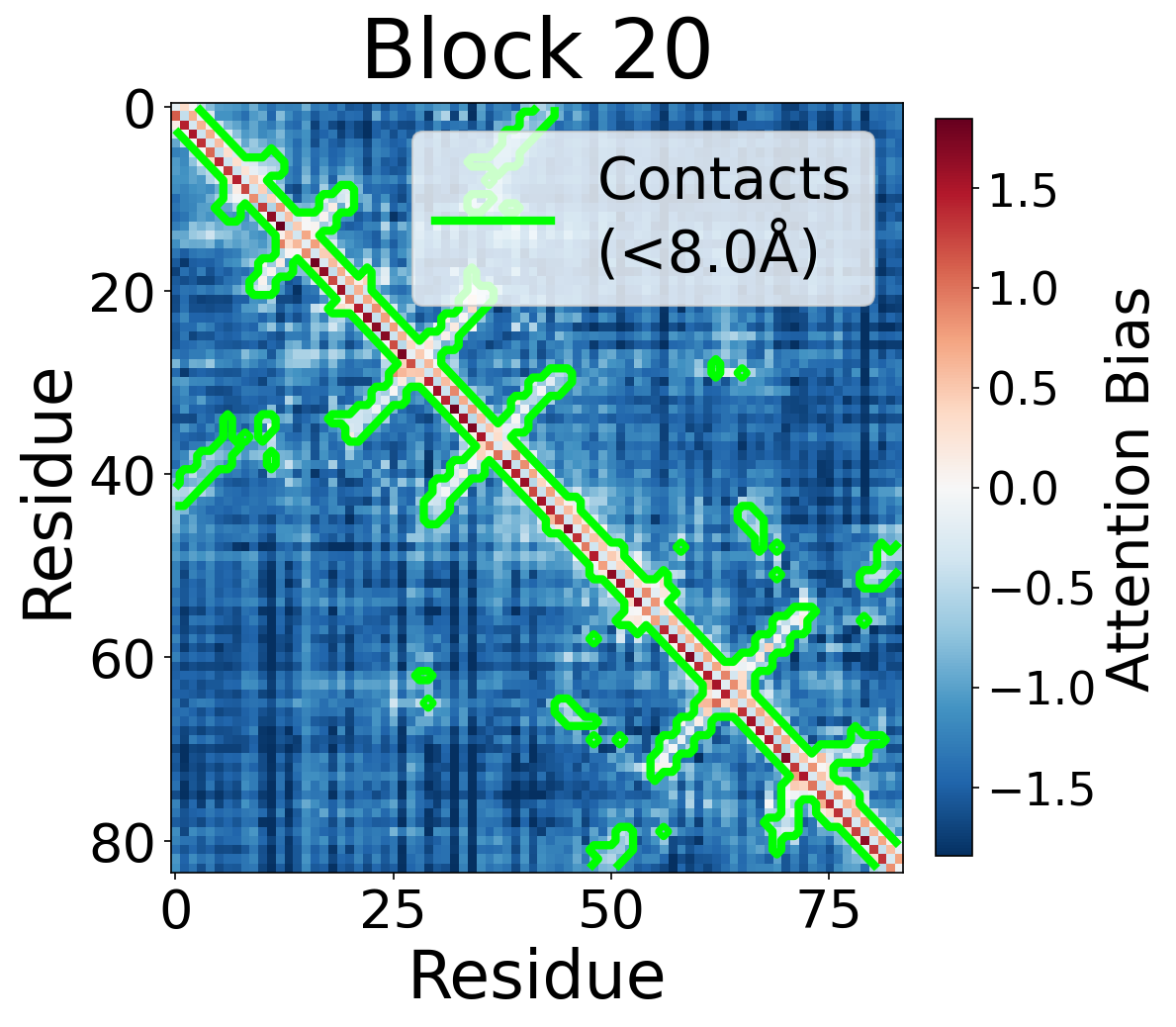

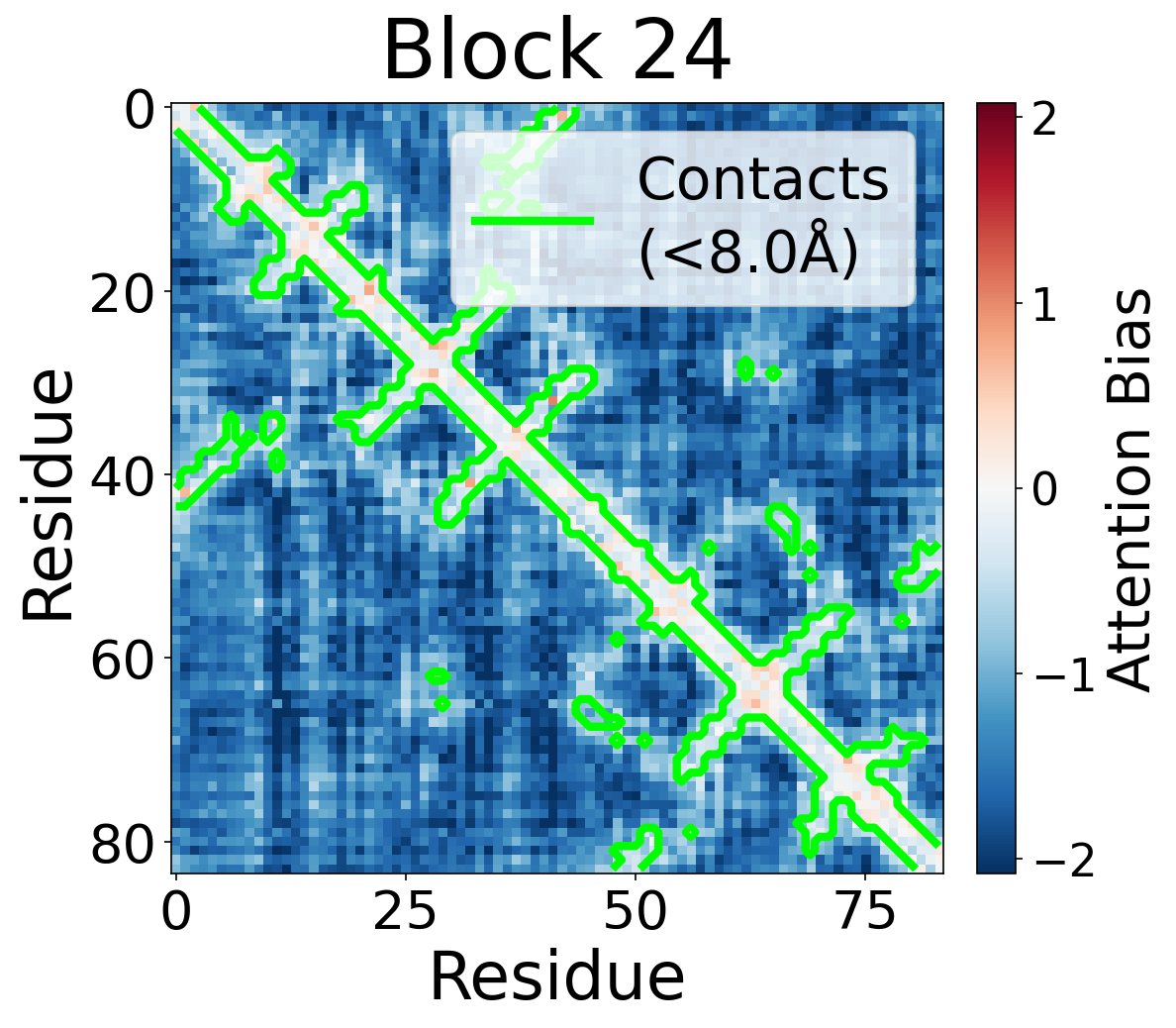

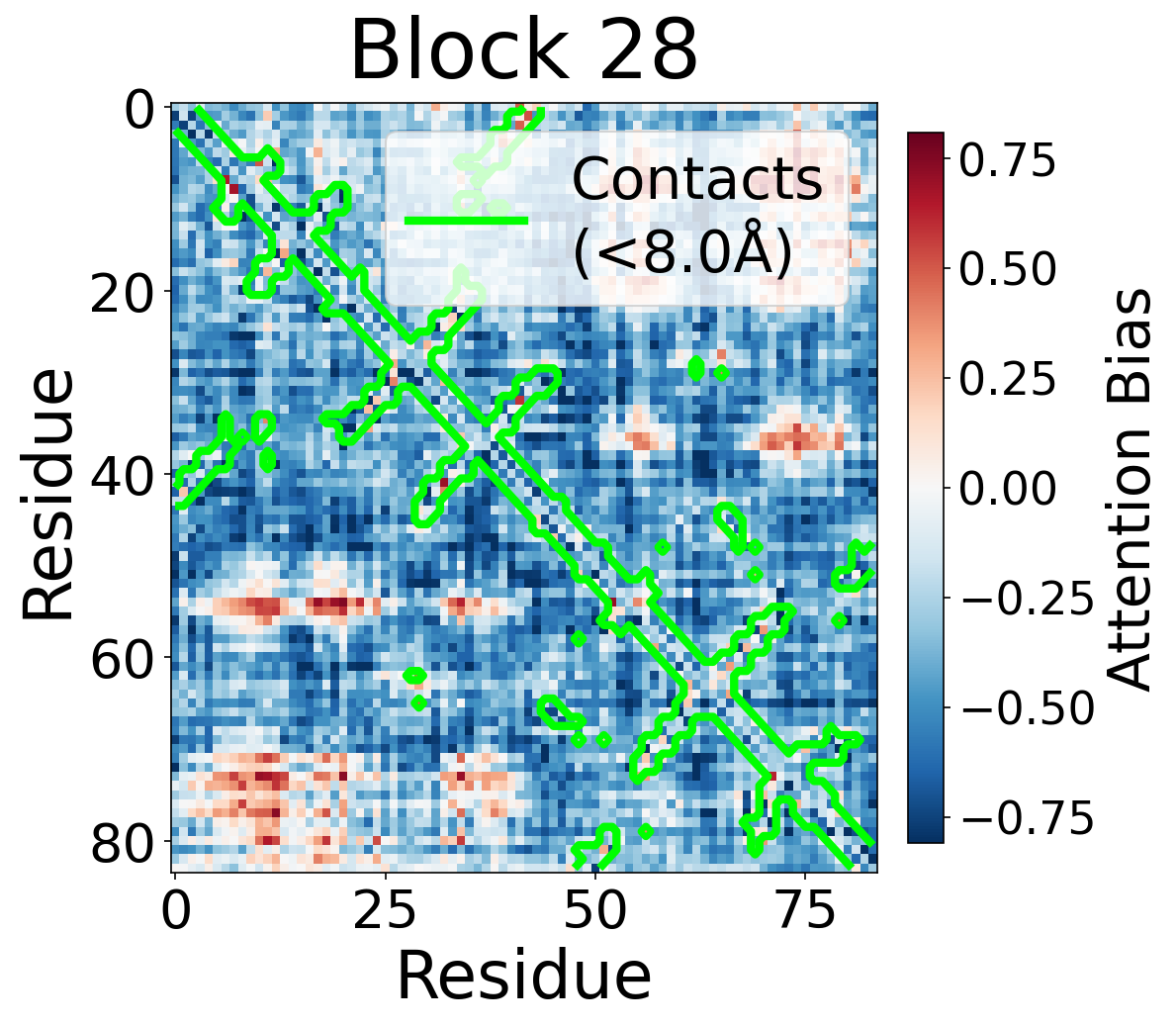

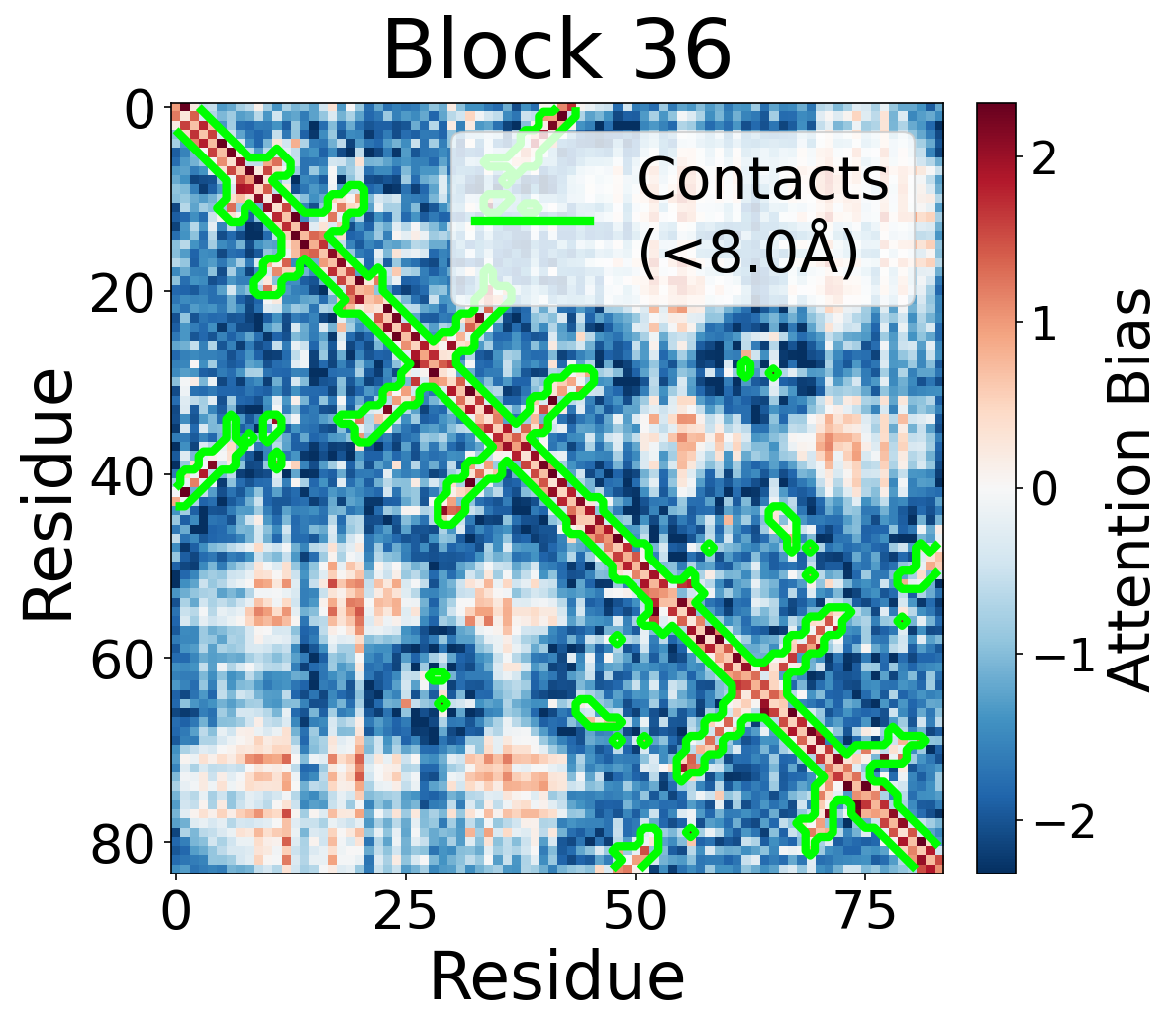

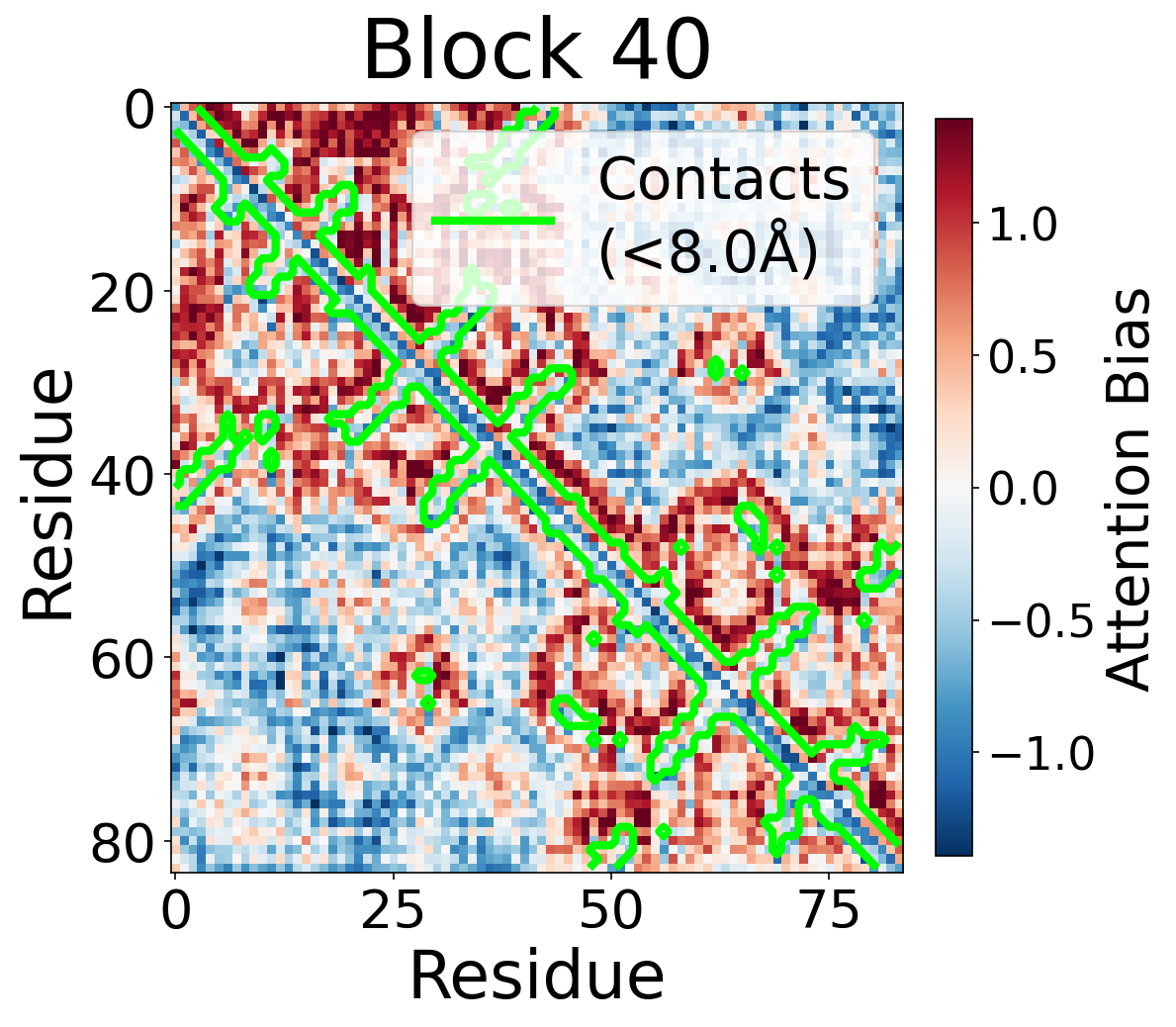

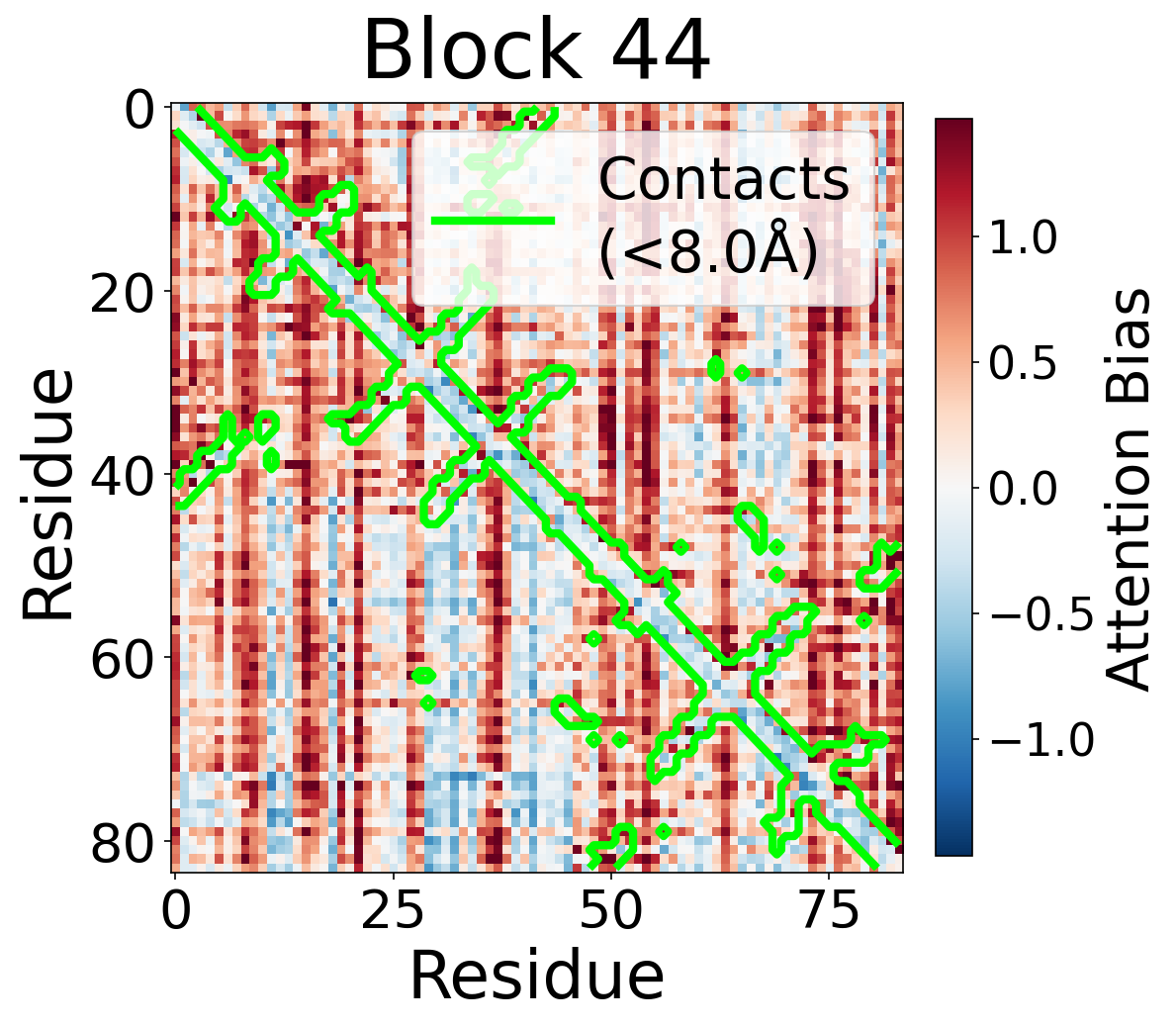

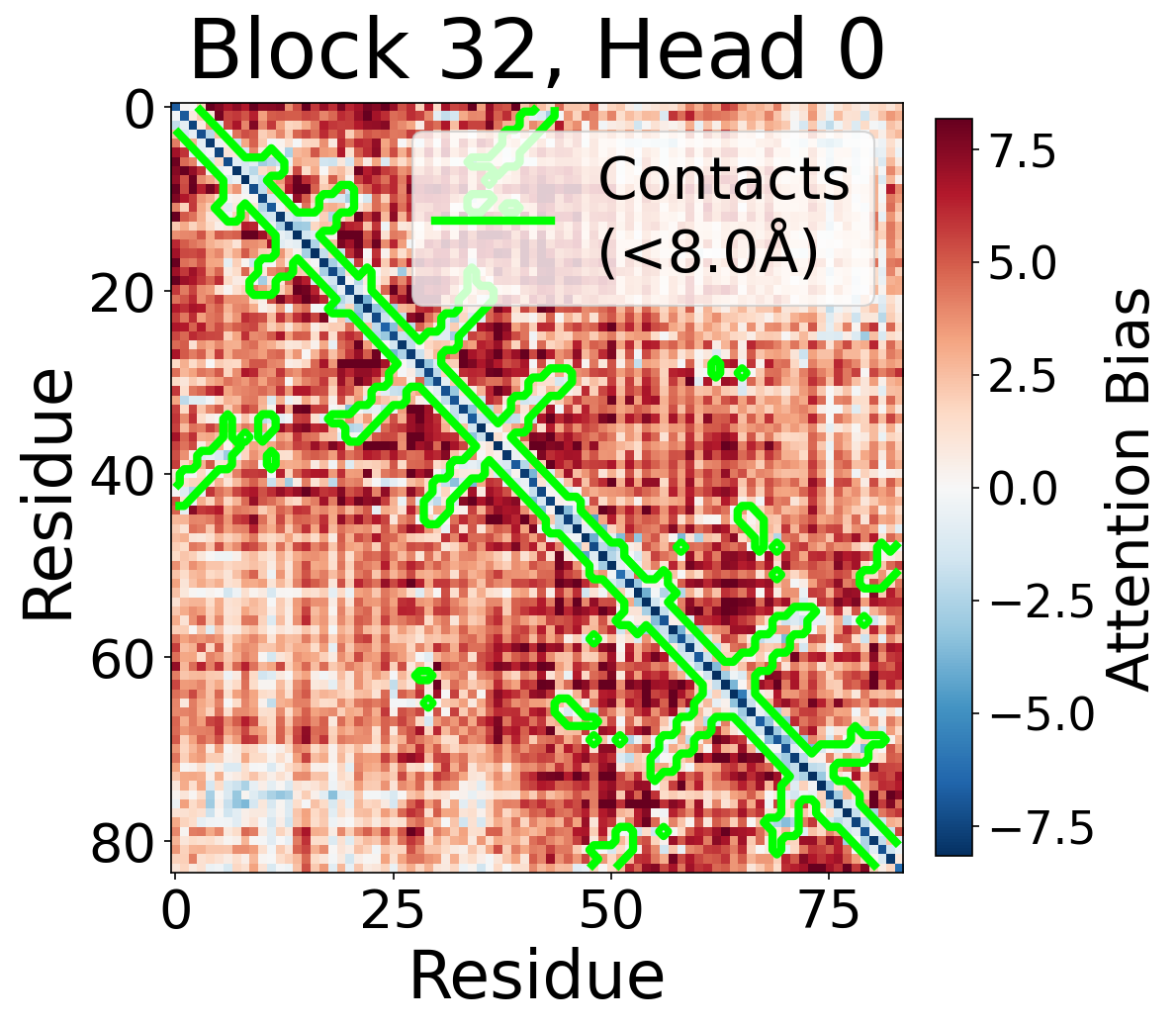

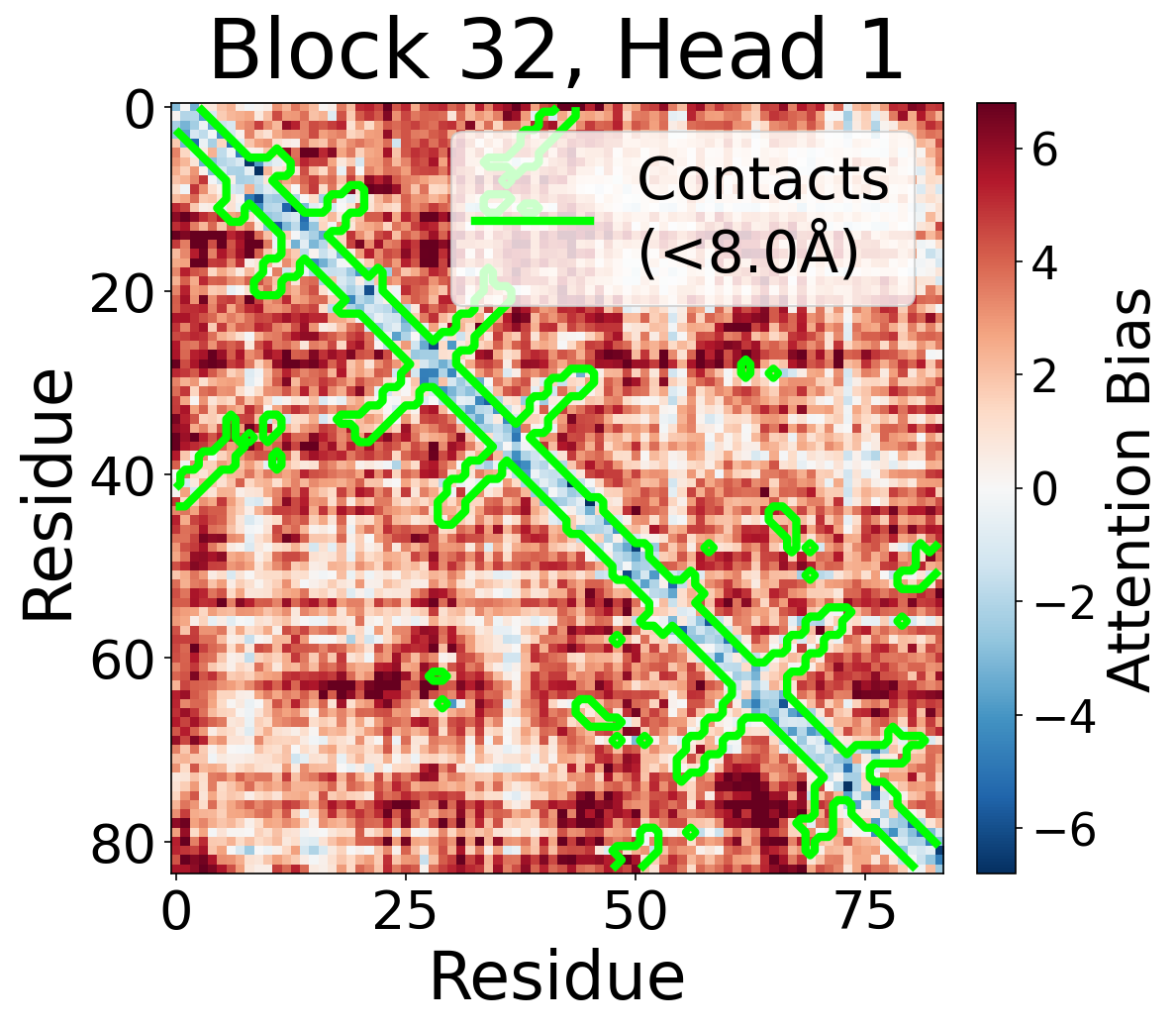

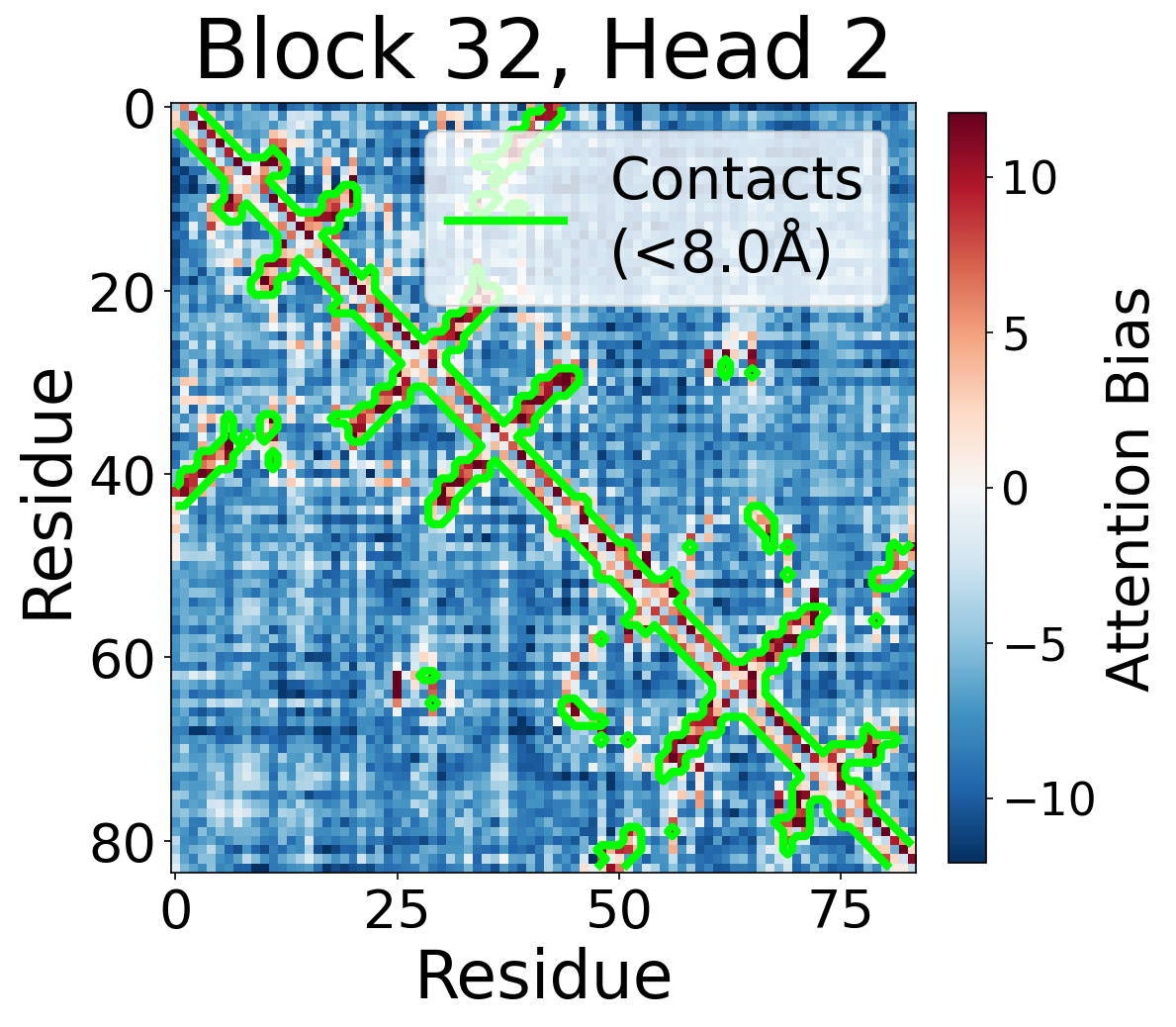

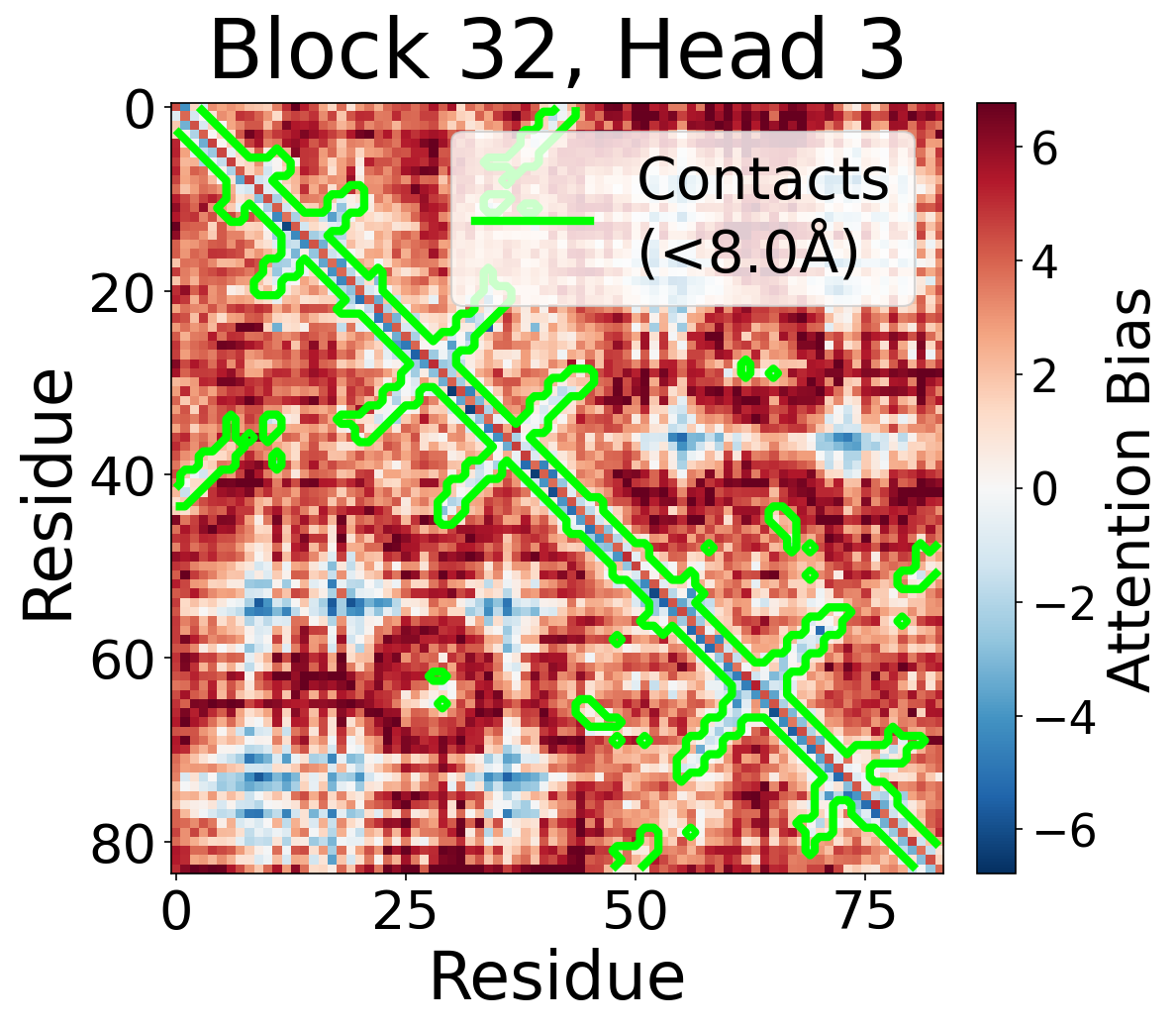

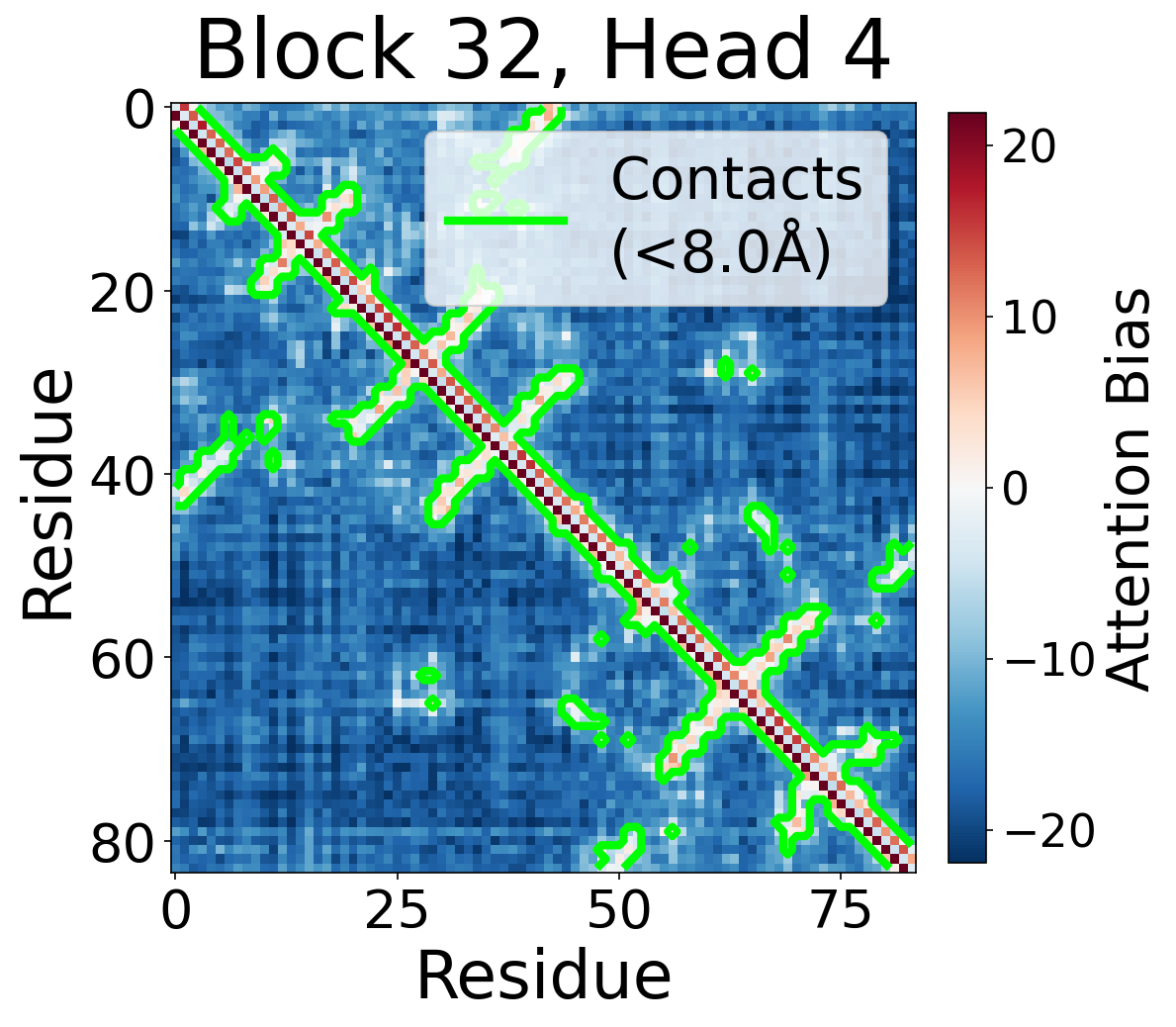

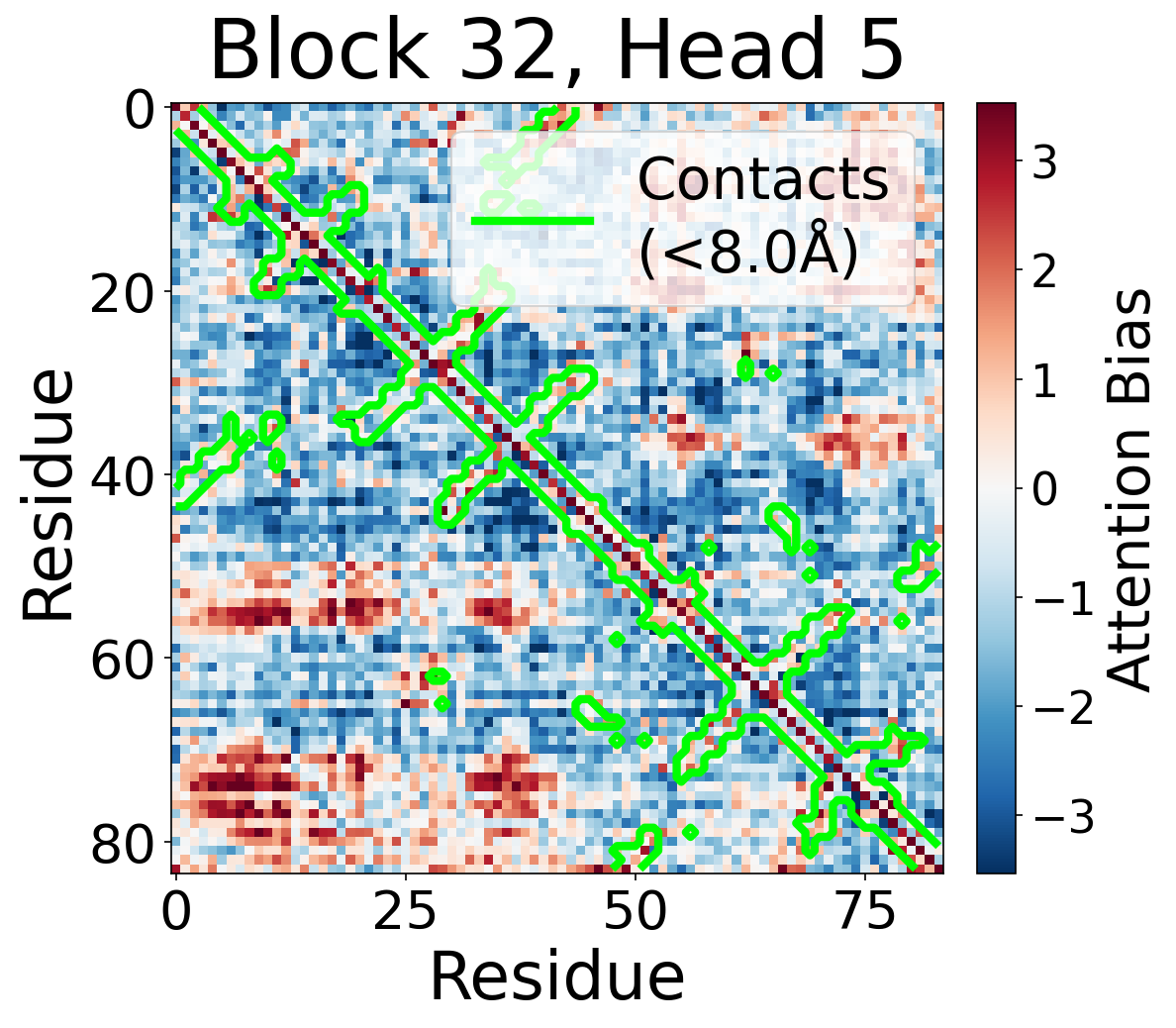

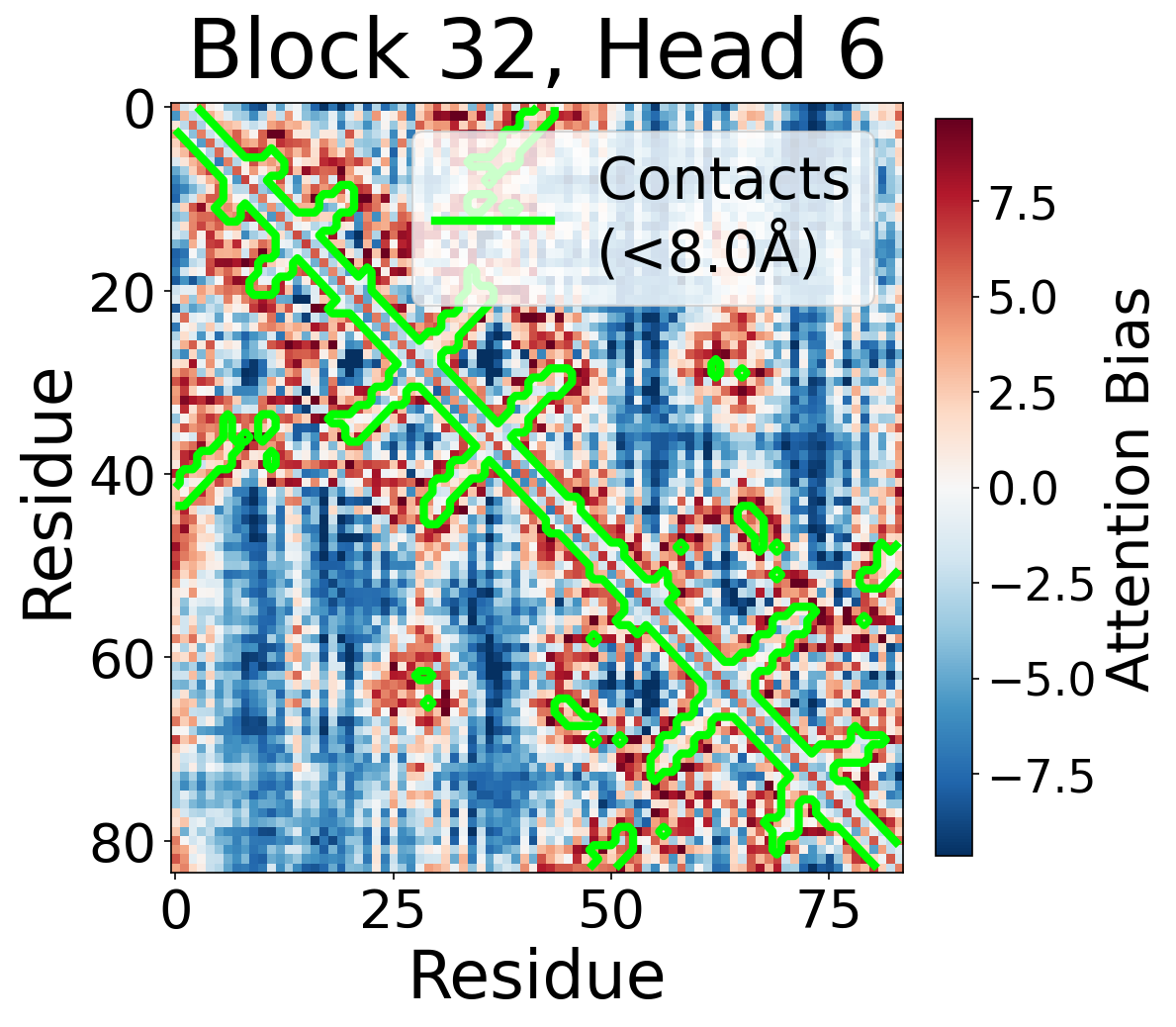

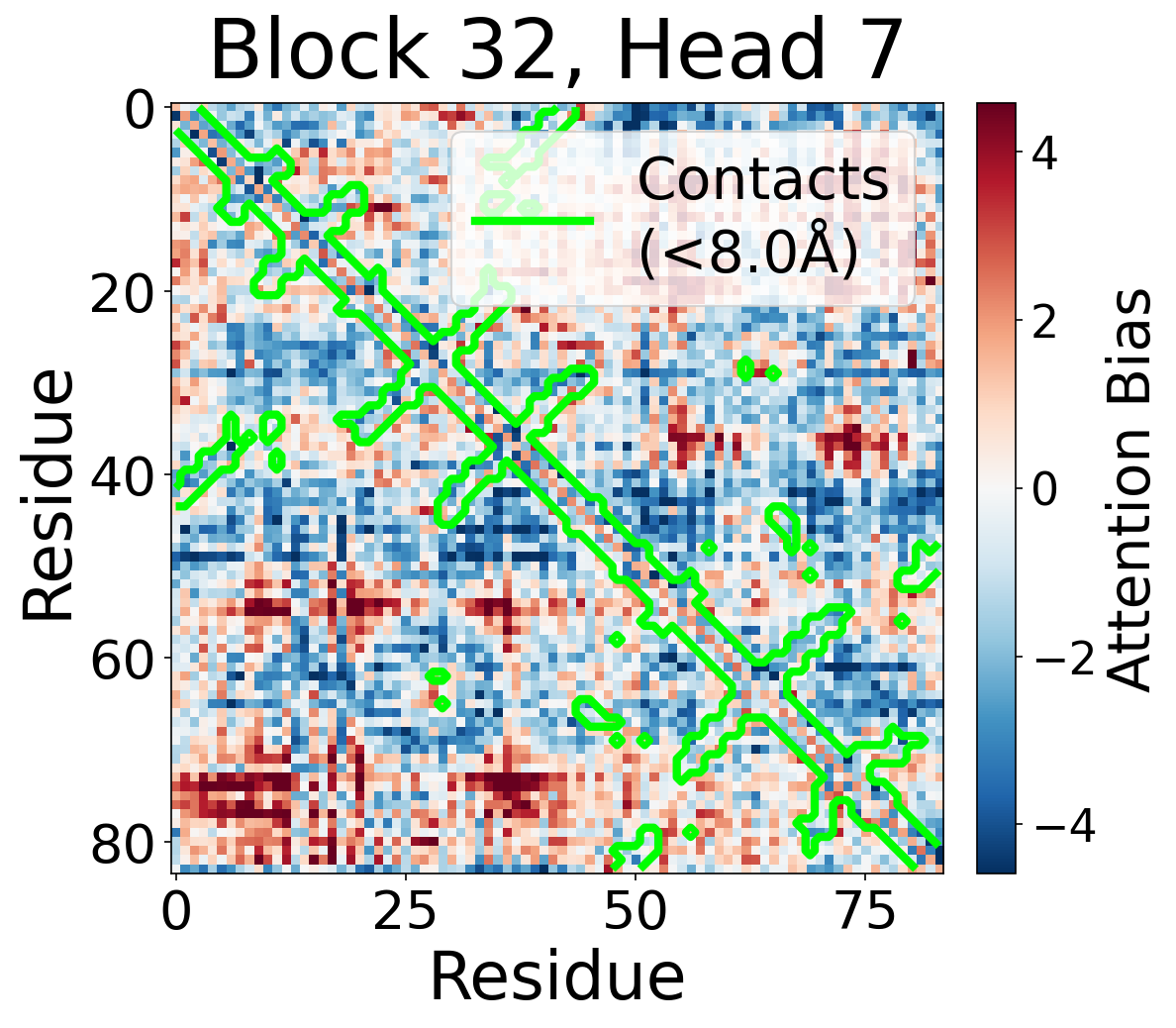

Appendix: Bias Maps

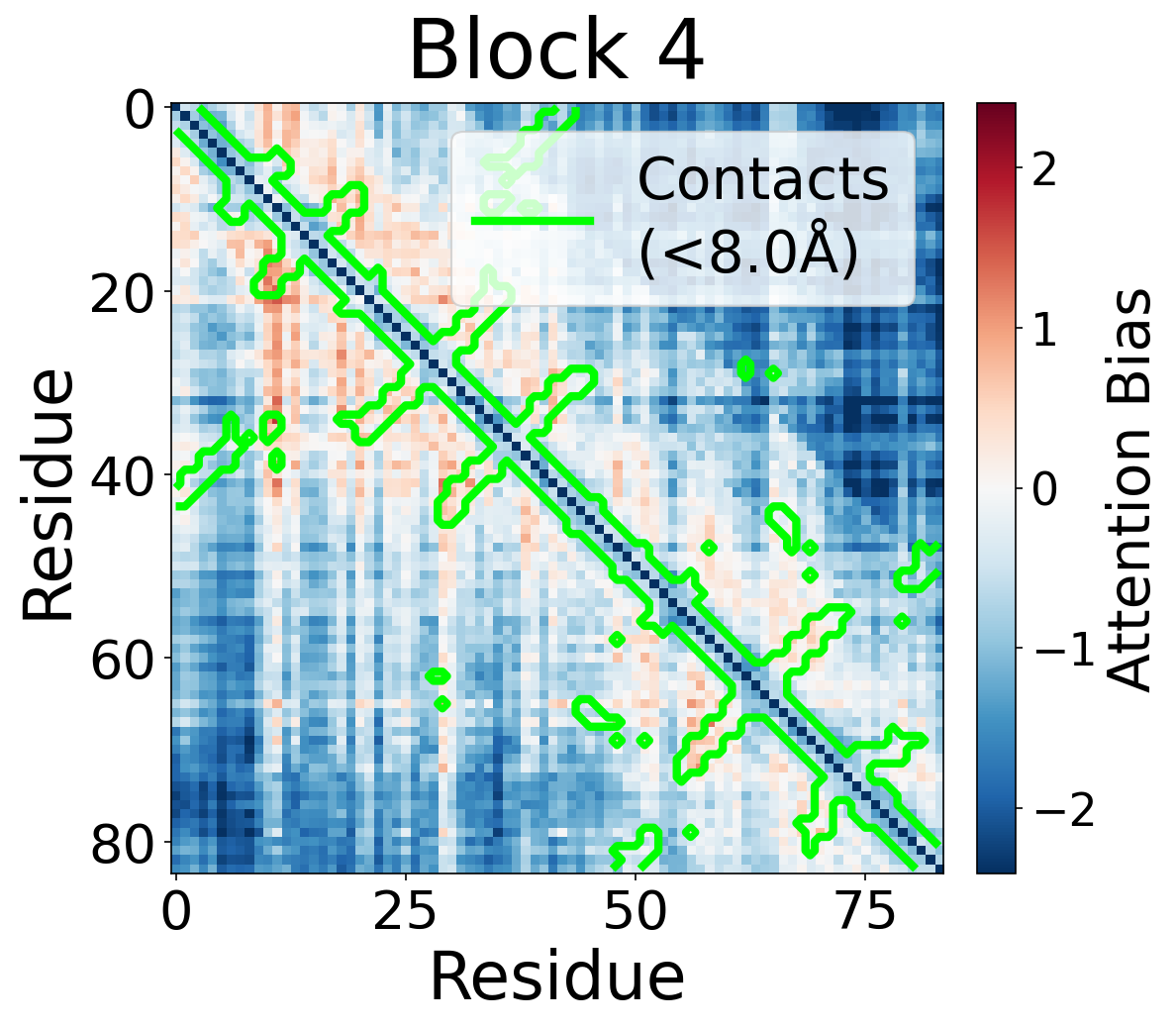

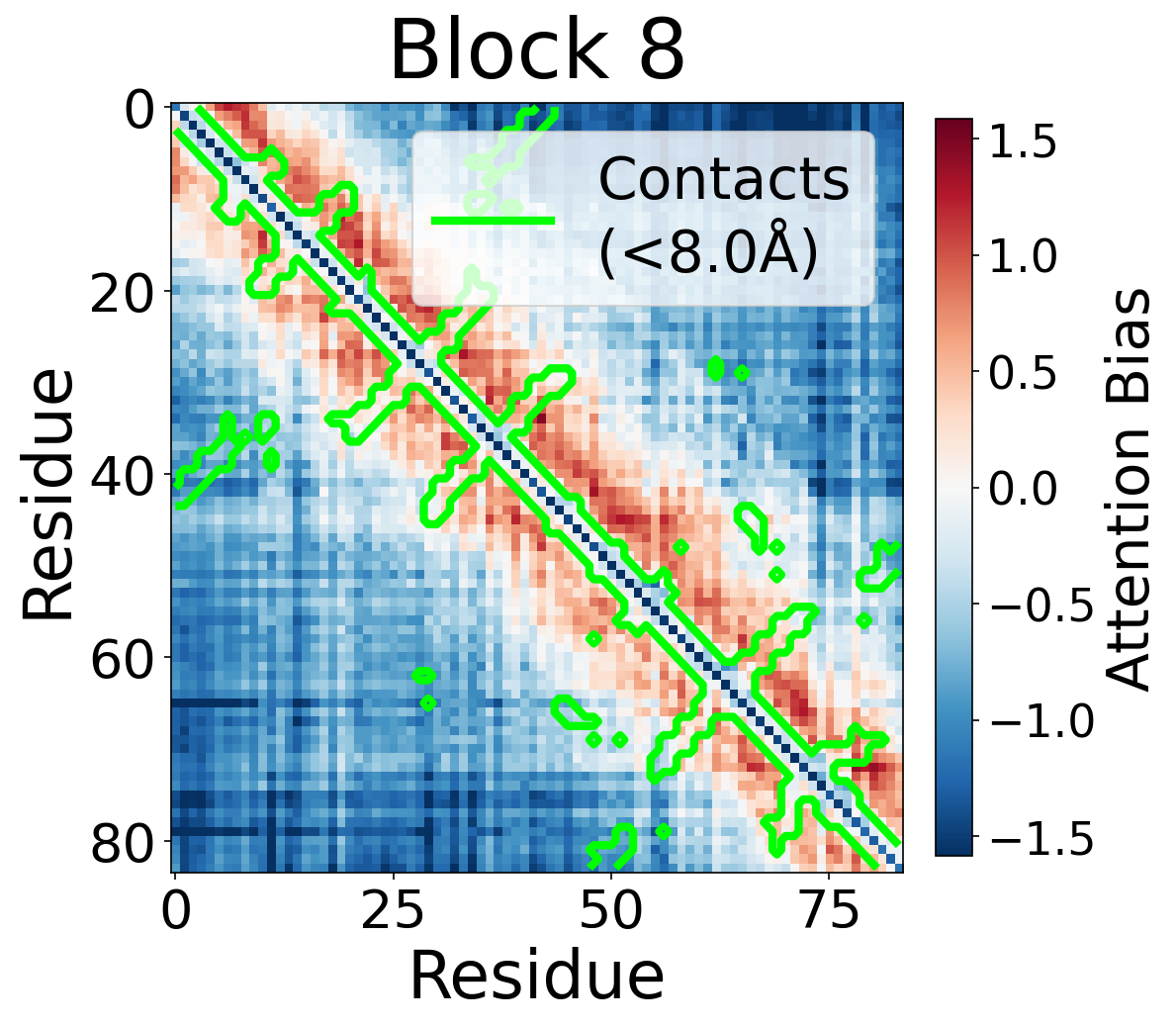

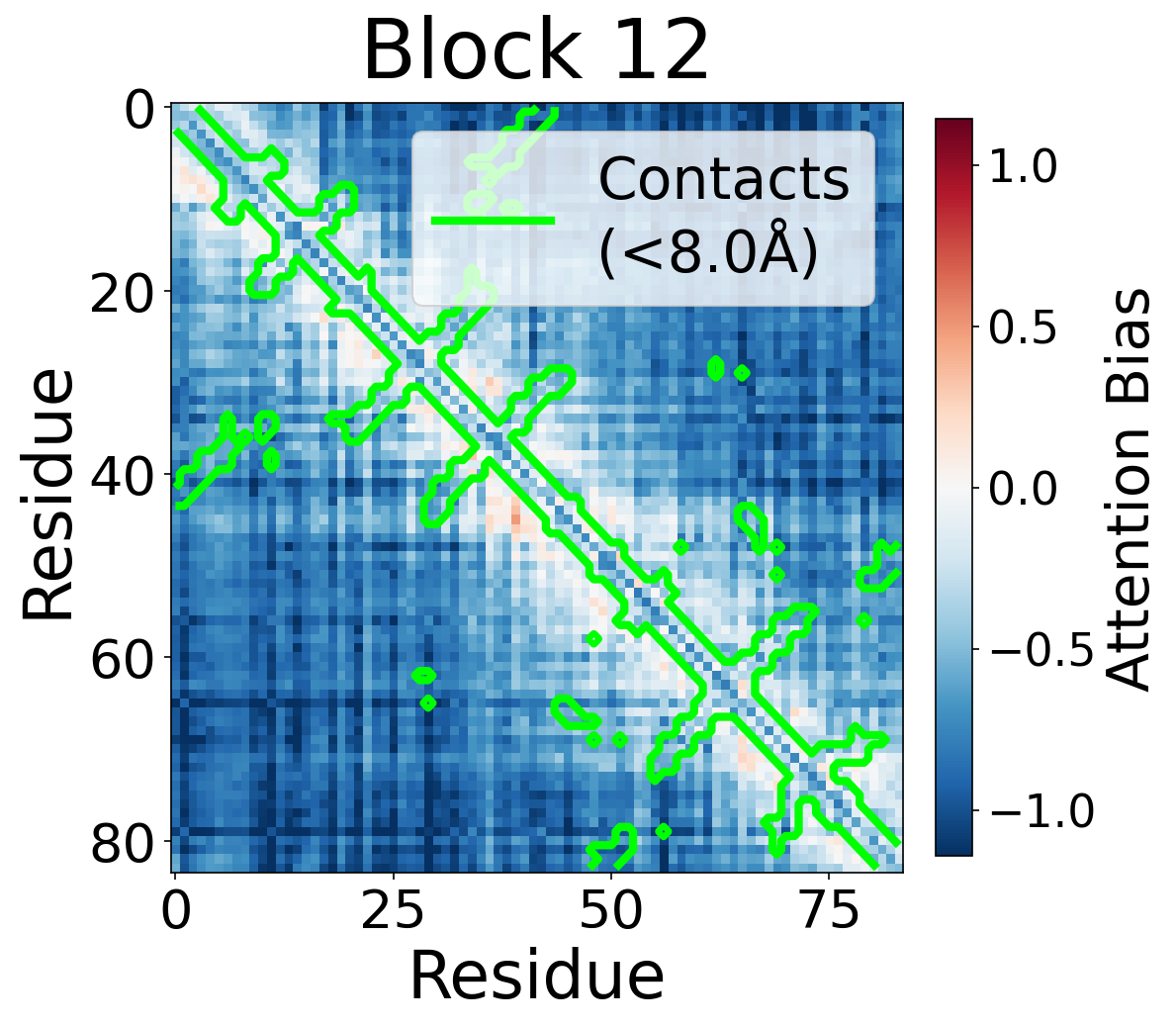

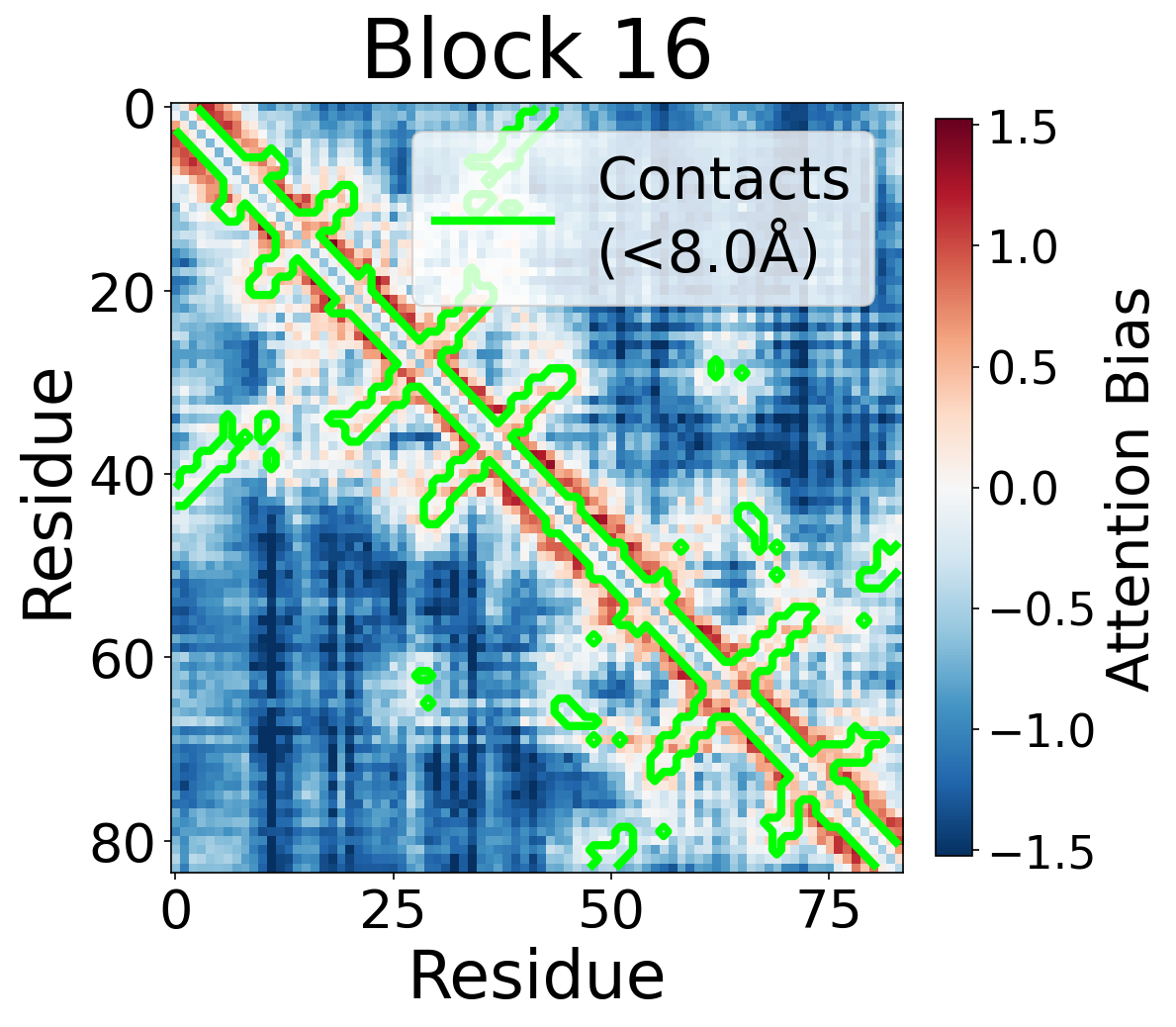

We visualize the pair2seq attention bias across blocks and across individual attention heads. For a single protein (PDB: 6rwc), we extract the bias term $\beta_{ij}(z_{ij})$ and average over heads. Green contours indicate structural contacts (C$_\alpha$ distance < 8Å).

Bias Across Blocks (Head-Averaged)

Each panel shows the bias term $\beta_{ij}$, averaged across all 8 attention heads, for protein 6rwc at selected blocks of the folding trunk. Red indicates positive bias (encouraging attention); blue indicates negative bias. In early blocks, the bias is near-uniform; by the middle blocks, it begins to align with the contact map, and by late blocks, contacting residue pairs receive substantially higher bias than non-contacts.

Block 0

Block 4

Block 8

Block 12

Block 16

Block 20

Block 24

Block 28

Block 32

Block 36

Block 40

Block 44

Per-Head Bias at Block 32

Individual attention head bias values for protein 6rwc at block 32. Different heads exhibit distinct patterns: some heads show strong contact-aligned bias, while others capture different spatial relationships or show more diffuse patterns. This specialization suggests that individual heads attend to complementary aspects of pairwise geometry.

Head 0

Head 1

Head 2

Head 3

Head 4

Head 5

Head 6

Head 7